The European Central Bank is set to unveil a new tool, the Transmission Protection Mechanism, which it hopes will protect states in the eurozone from escalating borrowing costs. Anthony Bartzokas, Renato Giacon and Corrado Macchiarelli argue there should be close coordination between the new mechanism and the implementation of the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility.

In the wake of deteriorating capital market trends, rising energy and food prices, and the war in Ukraine, policymakers in the eurozone face a difficult balancing act of trying to regain monetary and fiscal space without stifling Europe’s fragile economic recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic.

For fiscal policy, in particular, there is a growing consensus that policy should remain neutral – or even slightly contractionary – in the short term to aid efforts by the European Central Bank to tame the war’s inflationary pressures. At the same time, it is necessary to deliver targeted and temporary support to households most affected by the squeeze in real incomes.

The ECB has recently entered a tightening cycle following – with some delay – other major central banks, including the Bank of England and the US Federal Reserve. It is now pivoting toward more aggressive rate hikes in anticipation of higher inflation, and it is widely expected to begin normalising rates between July and September.

In addition, one important element of the ECB response to the war in Ukraine (which builds partly on its response to the Covid-19 pandemic) has been to give itself extra flexibility and discretion in buying eurozone sovereign bonds to help combat the widening of sovereign spreads and negative second round effects in the real economy, particularly in Italy. It has done so through the development of a new anti-fragmentation tool, the Transmission Protection Mechanism.

Yet, this new tool is problematic for two reasons. First, monetary policy is not designed to deal with regional differences; rather it should aim to meet a target for inflation over the eurozone economy as a whole. It then follows that – if we are prepared to accept that the eurozone is an ‘optimal currency area’ in the first place – ECB policy should not be redefined to meet intra eurozone regional macroeconomic differences.

Second, providing even more uncapped fiscal insurance via the European Central Bank will likely lead to even more moral hazard for individual governments. This issue leads us to the question of what role monetary-fiscal policy coordination should have in the eurozone. We have explored this in NIESR’s forthcoming Global Economic Outlook.

At the peak of the eurozone crisis in 2012, the ECB also unveiled a new tool, Open Market Transactions (OMTs), where the ECB agreed to buy a country’s sovereign debt as long as that country’s government agreed to strict conditionality. However, the conditionality attached to the programme, i.e., the need to negotiate a programme of reforms with the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), proved sufficiently onerous and politically difficult to prevent any member state from requesting it.

While other instruments such as the Commission’s SURE and the new ESM Pandemic Crisis Support instrument were agreed with fairly limited conditionality, they were both very narrow in scope and duration. SURE proved successful in deploying resources to protect jobs and incomes affected by the pandemic. However, the ESM initiative had little success as the stigma of conditionality seemed to extend to this new instrument as well.

This experience suggests that, should the ECB adopt the Transmission Protection Mechanism without conditionality, it could create the usual problem of moral hazard. If the ECB were prepared to buy unlimited amounts of debt, there would have to be conditions, similarly to OMTs. If the amount of debt purchases was limited ex-ante, markets would soon test these limits, as they did with the ECB’s Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP). An unlimited instrument without conditionality would open the door to more debt issuance, without a break clause.

Macro theory suggests that fiscal redistribution can help long-term debt sustainability in the absence of high labour mobility. Time and again, eurozone leaders have shown a willingness to redistribute liquidity and risk via the ECB’s balance sheet, while any steps towards stabilisation via fiscal redistribution remains taboo.

The Recovery and Resilience Facility is not a cyclical fiscal stabilisation tool

On the fiscal side, the biggest policy novelty since 2020 has been the Next Generation EU (NGEU) programme and its centrepiece, the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). These instruments are set up so that the deployment of EU funds is conditional upon the fulfilment of milestones and targets underpinning reforms and investments in the respective national recovery and resilience plans.

Furthermore, the national recovery and resilience plans are embedded in the European Semester, the EU’s framework for economic policy coordination, with the additional need to achieve ambitious green and digital targets. The mechanism represents external market discipline both in the funding and the investment framework, which finds a precedent only in the experience of some EU countries such as Greece under the Enhanced Surveillance Framework post-2010.

Recently, there have been calls for the ex-ante conditionality mechanism based on the Recovery and Resilience Facility milestones to be used in coordination with the new Transmission Protection Mechanism: this could represent an important development in the evolution of monetary-fiscal policy coordination in the EU. Yet, for now, the Recovery and Resilience Facility remains far from a fully-fledged EU budget with shock absorbing capacity. It has a long way to go before it can concretely support the ECB in fighting high inflation and/or prevent a deflationary spiral while supporting demand in the eurozone as a whole.

In particular, we think a more permanent Recovery and Resilience Facility loan component could be used as leverage for activating the ECB’s Transmission Protection Mechanism, given that loan demand is largely coming from the EU southern (Greece, Portugal, Italy, Cyprus) and eastern (Romania, Poland, and Slovenia) periphery who typically face tougher budget constraints.

This could be significant as the Recovery and Resilience Facility conditionality circumvents the usual more-hazard criticism by moving the goalposts from mutualising legacy debt to financing longer-term new (mainly capital expenditure related) investment opportunities. While reviews of Recovery and Resilience Facility milestones are political processes that take time and tend to happen at most twice a year – thus, representing an institutional process which might move too slow for markets – the process might not be procedurally lengthier than a potential ESM programme (such as Greece’s Third Adjustment Programme), had the OMTs been used.

More specifically, EU Recovery and Resilience Facility funds are being paid for by the European Commission by issuing new EU debt as Next Generation EU bonds, establishing for the first time a large-scale joint funding model. They are then transferred as grants and concessional loans to finance ministries at the national government level. According to early ECB estimates, Next Generation EU issuances will raise EU debt by a factor of roughly 15, making it the largest ever experiment in supranational euro-denominated debt sharing.

The Commission has had a very successful issuance journey to date, having raised 121 billion euros in long term funding over ten syndicated transactions and eight bond auctions as well as 58 billion euros in short term funding via the EU Bills programme. These, together, have enabled the disbursement of 67 billion euros in grants and 33 billion euros in loans to member states under the Recovery and Resilience Facility.

In June 2021, the 20 billion euros inaugural issue represented something of a landmark: the largest-ever institutional bond issuance in Europe, the largest-ever institutional single tranche transaction, and the largest amount the EU has raised in a single transaction. Furthermore, the Commission has recently launched the process for organising the settlement of Next Generation EU bonds through the payment and settlement infrastructure of the Eurosystem, to be aligned with the arrangements used by EU sovereign issuers and the ESM, whose bond transactions are settled in central bank money.

Strong interest has followed over the past several months as the issuance as Next Generation EU bonds provides an opportunity to buy into a ‘safe-haven’ while getting a marginal return over the German Bunds. The fact that more than 30% of Next Generation EU bonds will be green bonds is also expected to attract investors and could lead to considerable savings for the EU due to the lower spread over the benchmark.

The fast pace and large volumes may cause questions as to whether the Commission bonds can be fully absorbed by the market and how this will affect volatility and spreads, particularly at a time when the ECB has announced it will slow down the asset purchase programme, thus releasing alternative safe-haven assets, i.e., German bonds, that are typically considered ‘scarce’ because of the central bank’s demand.

However, from the point of view of market participants, the Recovery and Resilience Facility does not represent a shock absorbing device. Furthermore, it focuses on credit supply by financial intermediaries, leaving aside market-based solutions provided by non-financial corporations.

In fact, looking at the link between GDP growth and the Recovery and Resilience Facility funds, the correlation between these appears to be small, if not negative in some cases. In short, the EU still lacks a joint cyclical fiscal stabilisation tool. This could be achieved through a more permanent Recovery and Resilience Facility, which would have the potential to provide a financing buffer through concessional loans in case market funding becomes scarcer as the result of steeper borrowing costs.

Long-term implications of short-term challenges

Despite the limited interest to date in the loan component, the Next Generation EU and Recovery and Resilience Facility instruments have been estimated by the European Commission, the ECB, and the IMF to have led to an increase in GDP of up to 1.5%, relative to the baseline scenario for 2022.

The Recovery and Resilience Facility has been estimated to induce a debt-based fiscal expansion of 0.65% of GDP on average over the five years between 2021 and 2026, with countries that are among the scheme’s major beneficiaries, such as Italy and Greece, benefiting from an extra 3% and 2% of GDP, respectively, at the peak, relative to countries which have decided not to apply for loans. Currently, only seven EU member states (Greece, Italy, Portugal, Poland, Romania, Cyprus, and Slovenia) have requested loans amounting to a total of 166 billion euros out of the 385.8 billion euros available.

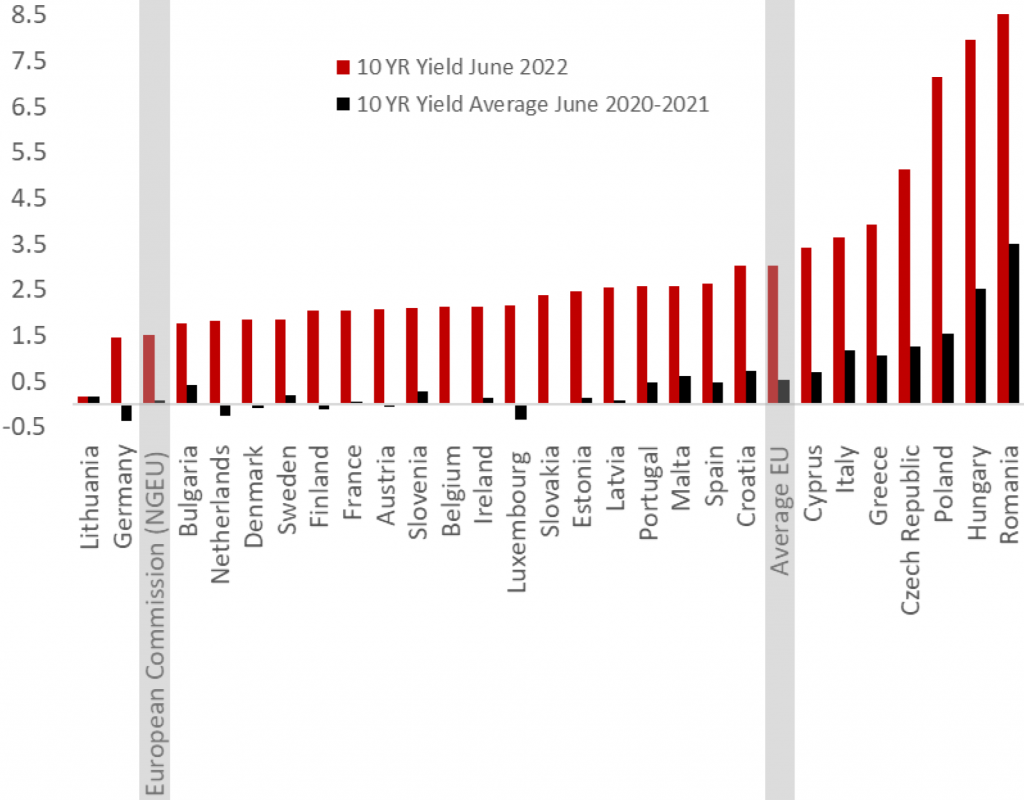

Politically, Northern European countries that have been grouped as the ‘frugal’ states (Netherlands, Austria, Finland, Sweden) have always made clear that they would prefer to opt out of the EU loans for now. More generally, from a financial point of view, other EU countries with a AAA rating, including Germany, may find it unappealing to borrow from the Commission – whose rating is still better than the rating of 22 out of the 27 EU member states – even if at concessional rates, as their national interest rates are still below or on par with the Next Generation EU Bonds (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Market yields of government bonds with maturities of ten years, and European Commission’s first and latest issuance under Next Generation EU, June 2022 (per cent)

Source: Authors’ elaborations based on data from the European Central Bank and European Commission. Data for the Next Generation EU bond refers to the weighted average yield at the corresponding 10-year maturity.

However, EU member states can still request loan support until 31 August 2023. As capital market conditions have deteriorated over the past few months following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, more EU member states will have incentives to request loans from their Recovery and Resilience Facility allocation.

This is a scenario that the European Commission and finance ministers could even welcome in the short to medium term, as there is a scarcity of new financial resources to cushion the effect of the economic and financial ramifications of the war in Ukraine. With national fiscal resources already overstretched and countries having achieved the annual upper ceilings of the EU Multiannual Financial Framework budget, the expectation in Brussels was that more EU countries would have requested Recovery and Resilience Facility loans (at concessional rates and with few strings attached besides the milestones of the recovery plans) from the Commission.

However, even countries such as Spain, Croatia, the Czech Republic, and Hungary, which have substantial funding needs and would borrow at substantially higher interest rates on the markets than the EU Next Generation EU bonds, have preferred to stay put and only request grants for the time being. Other countries such as Poland, Cyprus and Portugal requested only small amounts of their Recovery and Resilience Facility loan allocation considering legacy issues of delayed implementation and monitoring requirements.

With interest rates currently rising and bond spreads widening once again within the eurozone, it is likely more governments will avail themselves of Recovery and Resilience Facility loans. Should an increasing number of EU member states tap into the full amount of Recovery and Resilience Facility loans to which they are entitled (i.e. equal to 6.8% of their 2019 Gross National Income), the Commission’s borrowing on financial markets would need to match that of the largest eurozone sovereign borrowers (Italy, France, Germany and Spain) over the next few years – while it was still trailing behind them in terms of gross issuance in 2021.

If countries opt to request the entire loan allocation to which they are entitled, this could therefore have important ramifications on the EU’s funding strategy. It could even break the upper threshold of the funding targets that the Commission has set for itself in terms of bond issuance on the markets, the initial 385.8 billion euros Recovery and Resilience Facility loan component (at current prices) envisioned in the Recovery and Resilience Facility Regulation (for sake of illustration, a conservative loan allocation, excluding Austria, France, Finland, Germany, Luxemburg, the Netherlands, and Slovakia would still result in a total Next Generation EU loan allocation in excess of the allotted 358.8 billion euros).

This scenario underscores the potential complementarities of the ECB’s Transmission Protection Mechanism tool with the Recovery and Resilience Facility. First, policy innovations in the Recovery and Resilience Facility could provide a conditionality framework to support the design of the Transmission Protection Mechanism.

If the smoothing of credit supply shocks is indeed a priority for monetary policy, the Recovery and Resilience Facility concessional loans could provide sufficient space to financial intermediation and help reignite long-term growth, provided that the ECB’s Transmission Protection Mechanism tool neutralises the emergence of an unjustified “diabolic loop” in European countries more at risk – not only in the Southern but also the Eastern EU periphery more affected by the war in Ukraine.

The one problem with the Recovery and Resilience Facility acting as a supplement to the ECB’s Transmission Protection Mechanism tool is that the Recovery and Resilience Facility is expected to be a one-off and is narrow in scope. Furthermore, the window for applying for the Recovery and Resilience Facility loan component lasts until August 2023. EU policymakers might therefore find an agreement on the need to make any Recovery and Resilience Facility type funding more permanent with the capacity to also finance other priorities (including current expenditure items).

Importantly, such interactions would represent a viable alternative to making the ECB’s Transmission Protection Mechanism strictly conditional on adherence to the reformed EU fiscal rules. The one problem seen in the past with a direct link to the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) was that it made the EU’s fiscal rules extremely political and sanctions through the Reverse Qualified Majority Voting (RQMV) very difficult to achieve.

Should the Transmission Protection Mechanism and a permanent-style Recovery and Resilience Facility loan facility be linked, conditionality would come from market discipline. Most of the underlying loans to the final beneficiaries in the real economy would be channelled via international financial institutions, commercial banks, and private investors, thus increasing competition. Also, in the absence of compliance with Recovery and Resilience Facility loans’ milestones, the ECB would simply stop buying bonds through the Transmission Protection Mechanism.

A stand-alone Transmission Protection Mechanism will come at a cost to the ECB’s monetary policy credibility and could potentially add to moral hazard in debt markets. The main point is its conditionality. While the tool may reduce fiscal risks and support the creditworthiness of these sovereigns over the short term, progress over debt stabilisation will remain key to the eurozone’s long-term sustainability.