The campaign for Latvia’s parliamentary election on 1 October was dominated by the war in Ukraine. Daunis Auers reflects on what the results of the election might mean for the country’s future.

That hoary old academic chestnut of ‘continuity and change’ captures the essence of Latvia’s 1 October regular parliamentary election. On the one hand, the election delivered yet another parliamentary majority to a centre-right coalition of new and old political parties that will be firmly Atlanticist, pro-European, nationalist and heroically battle to unleash Latvia’s under-performing economy. On the other hand, Latvia’s biggest party, the Russophone left-leaning Harmony Social Democracy (Saskaņa, SSD), the winner of the largest share of the vote in the last three parliamentary elections, failed to pass the 5% threshold.

Indeed, four parties and party alliances that together took more than 60% of the vote in the 2018 parliamentary election – the Conservatives (Konservatīvie, K), Who Owns the State (Kam Pieder Valsts, KPV) and Development/For! (Attīstībai/Par!, AP) as well as SSD will not be represented in the parliament, where two-thirds of deputies will be new to the job.

The campaign

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February altered the trajectory of the election. January 2022 polls had shown Prime Minister Krišjānis Kariņš’ New Unity (Jaunā Vienotība, JV) party languishing in third place, well behind SSD, with the support of 7.5% of the electorate.

Both Prime Minister and party were jaded after three tiring years in office dominated by the challenges of Covid-19 pandemic management and intra-government bickering between the five (later four) ideologically diffuse parties that had taken almost four months to hack together a governing coalition agreement. Opposition parties were making gains by focusing on Latvia’s recent sluggish economic growth and criticism of the government’s handling of the pandemic. Change was in the air.

However, the war in Ukraine left opposition parties floundering and none more so than the Russophone SSD, whose leadership was surprisingly quick to speak out against the Kremlin’s war. This, however, put them out of step with the majority of Russian-speakers in Latvia.

An April poll by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation found that a majority of Russian-speakers were still not taking any side in the war (although 51% of Russian-speakers aged 18-24 were supporting Ukraine). This ‘neutrality’ is largely interpreted as support for Russia. In contrast, 83% of ethnic Latvians vigorously supported Ukraine. This disconnect between party and electorate created a space for more virulently pro-Kremlin parties to appeal to the Russian-speakers who were long locked into supporting SSD.

The youthful Stability (Stabilitāte, S) party, founded in January 2021 by Aleksejs Roslikovs who had been kicked out of SSD, successfully utilised social media to run a populist campaign that focused on anti-Covid lockdown and anti-vaxxer memes and refused to criticise Russia’s war in Ukraine. Latvia’s Russian Union (Latvijas Krievu Savienība, LKS), a more established pro-Kremlin party led by ageing figures not entirely dissimilar to the Soviet politburo in the early 1980s, was weakened by internal splits between leaders and failed to match the viral campaigning energy of Stability.

All three Russophone parties criticised the government’s post-Ukraine war policies of accelerating reforms that would see all Russian-language public schools switch to teaching in the Latvian language by 2025, the marginalisation of the Russian language in public places (such as removing the Russian language sections from public sector home pages) as well as the dismantling of all pro-Soviet public monuments by November this year, including the monolithic ‘Victory Monument’ pillar in Riga which was toppled in August. However, an online poll shortly before the vote indicated that young Russian speakers were drawn more to the social democratic Progressives (Pro), which had both ethnic Russian and Latvian leaders, than the established Russophone parties.

The key dilemma for JV’s three government coalition partners, the National Alliance (NA), the Conservatives and AP, was how far to distance themselves from the Prime Minister. AP’s candidate for Prime Minister, the Defence Minister, Artis Pabriks, took to personally attacking Prime Minister Kariņš’ leadership style. In contrast, the Conservatives defended the government’s record. However, both saw their vote collapse and they each finished below the 5% threshold. The radical right NA, which has long been tough on Russia and Latvia’s Russian-speakers, campaigned on an “I told you so” platform, promising more de-russification policies and continued support for Ukraine.

Other opposition parties were also left flat footed by the war. Former Deputy Prime Minister Ainārs Slešers’ Latvia First party (founded in 2021 and at least the fifth political vehicle he has created in the last quarter century) had advocated deepening economic ties with Russia and vigorous opposition to the government’s Covid-19 vaccination and lockdown policies. Both were made largely irrelevant by the war.

Controversial smalltown mayor and ‘oligarch’ Aivars Lembergs, who has been found guilty of corruption and influence peddling by a first instance court and even served some prison time before being released on health grounds (and has also been personally sanctioned by the US government), returned to front-line politics as the Prime Minister candidate of the Green/Farmers Union (ZZS).

ZZS had floundered after a number of key parties in the union had defected to a new business-friendly United List (Apvienotais Saraksts, AS) led by businessman Uldis Pīlēns. Lembergs, a long-time critic of NATO (he once described the alliance’s presence in Latvia as an “occupation”), the EU and the United States, simply turned tail and positioned himself as the biggest supporter of western interests in the country. Dressed in his trademark blaze of festive colours, he drew a sharp contrast with the dark suit/white-shirt/red-tie brigade of mainstream politicians. He blustered his way through debates and strengthened his core populist appeal among rural and smalltown voters.

In contrast, Prime Minister Kariņš avoided all leader debates (arguing that he would not debate with Lembergs and/or had no time on his schedule) until the last few days of the campaign. When he did finally appear in the dozen-strong scrum of leaders polling above 2% in the polls that were invited to the debates, the tall, slender Kariņš loomed over the bickering politicians surrounding him and often seemed to be the only adult in the room. He was the resounding victor of the final debate on public television. JV’s Foreign Minister Edgars Rinkevics’ unrelenting support for Ukraine and hawkish position on Russia saw his popularity similarly increase and JV won the biggest share of the vote with ease.

The results

The final results reflected polling trends as well as the exit poll. JV won more than a quarter of the seats in parliament and four centrist Latvian parties won a total of 64 seats. Kariņš clearly had a mandate to form a new government and the support of President Levits, who will formally nominate a candidate for the post in early November. Agreement on a new coalition was swiftly reached with NA and AS. However, JV and the President would also like PRO to be included in the coalition, but AS and NA would prefer to keep it as a minimal three-party coalition, arguing that PRO, as a self-declared party of the left, is too ideologically divergent to join the coalition.

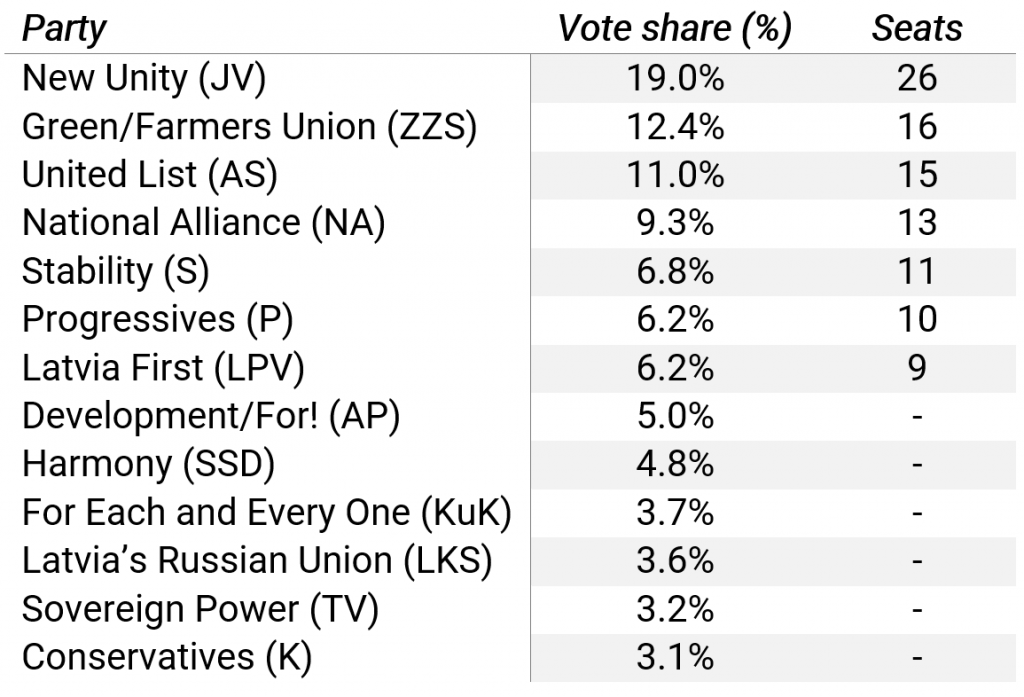

Table 1: Results of the 2022 Latvian parliamentary election

Note: Only parties that received more than 2% of the vote are shown. Figures rounded to one decimal place. Source: Latvian Central Election Commission.

Stability has replaced SSD as the Russophone party in parliament. AP and the Conservatives also finished outside the 5% barrier. After previous elections, SSD, AP and the Conservatives may well have collapsed and disbanded. However, generous state-financing of parties, introduced after the 2018 election, will likely allow the parties to live to fight another day.

Turnout rose by five percentage points to 59.5%. However, there was low turnout among the diaspora: 162,000 voters live abroad, making up around 12% of the electorate, yet turnout was just 16.1%. The eastern district of Latgale, particularly its urban areas which are dominated by Russian-speakers, voted very differently to the rest of Latvia, with Stability coming top with 18% of the vote.

Attention now turns to construction of the new government coalition. It is unlikely to take the three and a half months that was needed after the 2018 election, particularly with a war raging in Ukraine, and with Kariņš as the only obvious candidate for Prime Minister. While the new government will have to deal with a populist parliamentary opposition, this has been the norm in the thirty years of Latvia’s renewed democracy.