What role does discontent with democracy play in support for the far right? Drawing on new research, Daphne Halikiopoulou and Sofia Vasilopoulou show that democratic discontent can fuel support for far-right parties, but this relationship varies depending on voters’ attitudes toward immigration.

Does democratic discontent drive far-right party support? Existing research focuses on the common features of the typical far-right voter, who is likely to be a lowly educated, male individual with strong anti-immigrant attitudes and poor prospects in the labour market.

This individual is also likely to be discontent with the democratic process and distrust political institutions. Empirically, however, findings are conflicting with regards to the relationship between low trust in institutions and far-right voting as certain individuals who evaluate the democratic process positively may also vote for the far right.

In a new study, we offer a theoretical and empirical reassessment of the association between evaluations of the democratic process and far-right party support, taking into account the heterogeneity of the far-right voter pool. We identify two routes to far-right voting: discontent and ideology.

On the one hand, discontented voters who negatively evaluate the democratic process are more likely to be motivated by the desire to express their dissatisfaction and vote primarily against the system as opposed to in favour of the far right. On the other hand, voting for the far right is not exclusive to discontented voters. The mechanism here is ideology: ‘nationalist’ core voters are principled and support the far right because they identify with the entirety of its platform, which centres on prioritising in-groups over out-groups in every policy domain.

Democracy and discontent

Organised democratic society is best understood as a framework of collective cooperation that involves a trade-off between individual freedoms and collective payoffs. Citizens experience democracy through their everyday interactions with institutions: public benefits, the quality of local hospitals and schools, corruption, neighbourhood crime levels or the conditions determining employment security.

Their perceptions of how state resources are extracted and utilised, and what makes decisions as per the use of these resources legitimate, are inextricably interwoven with their perceptions of their interactive experiences. Citizens assess two components of the democratic process. First, the diffuse, which refers to broad support towards the democratic system, expressed through trust in institutions; and second, the specific, which refers to satisfaction with system performance and policy outputs.

The extent to which citizens trust institutions and expect effective policies is likely to shape their voting preferences. Declining institutional trust and negative evaluations of system performance and policy outputs are likely to damage mainstream parties, which become associated with the poor policy choices that negatively impact on citizens’ personal everyday experiences. Voters with low or declining levels of trust, as well as those voters who negatively evaluate system performance and policy outputs, are likely to reward political parties that challenge the establishment and existing political norms.

Protesters and nationalists

Far right populist parties are among the prime beneficiaries of these processes. These parties offer nationalist solutions to all socio-economic problems, centre on a purported conflict between in-groups and out-groups and put forward policies that always prioritise the in-group over the out-group in a quest to forge and maintain the homogeneity of the nation.

They challenge the establishment, both in terms of their populist component, which questions the legitimacy of elites, and their anti-liberal democratic component, which questions the existing mechanisms of democratic representation. Research has shown that far-right parties are often electorally successful in contexts of low quality of government and democratic discontent.

Empirically, however, voting for the far right is not exclusive to discontented voters. Consistent with the idea that political parties often receive electoral support from a broad range of voters, it is both theoretically and empirically possible that far-right core voters behave differently to peripheral voters. While the latter are often motivated by protest and the desire to express discontent, core voters are more likely to be ideological.

Who are the core far-right voters? We relate anti-immigration attitudes directly to the core far-right party ideology, which combines nationalism with xenophobia. The primary far-right party target constituency includes voters who identify fully with the far-right parties’ nationalist-xenophobic platforms. These voters tend to have strong nationalistic attitudes, accompanied by unfavourable attitudes towards immigrants who they view as a threat to the homogeneity, security and prosperity of the nation-state.

Core far-right voters prioritise the protection of the in-group from the out-group and vote ideologically based on a principled endorsement of far-right party agendas. The voting behaviour of these individuals is likely to hinge on questions of deservingness and selective solidarity, i.e. questions about entitlement to the collective goods of the state.

To theorise this, we draw on work which conceptualises the nation as an ‘imagined community of solidarity’. Individuals with strong nationalist and anti-immigrant attitudes are more likely to oppose sharing public goods with ethnic ‘others’. They have a narrower perception of deservingness because they are more likely to see the state and its institutions as benefitting the native majority.

Such individuals are more likely to support a conditional version of the welfare state that differentiates access between immigrants and natives. Therefore, positive evaluations of the democratic process among some individuals with anti-immigrant attitudes are likely to translate electorally into voting for parties that emphasise restricting institutional access to the in-group.

We show this empirically using data from nine waves of the European Social Survey (2002-2008). We commence by comparing far-right to non-far-right voters (Figure 1) to identify how the former score vis-à-vis the latter on their evaluations of the democratic process. This analysis illustrates that, on average, far-right voters are not substantially more discontented compared to non-far right voters.

With regards to the diffuse component, differences between far-right and non-far-right voters are small. These differences are even less prominent when it comes to the specific dimension. Interestingly, a significant share of far-right voters perceive the framework of collective cooperation to be working well. Yet, the mean differences in these evaluations between the two groups are statistically significant, which suggests that the effects of these measures on voting behaviour might also differ.

Figure 1: Comparison of evaluations of the democratic process between far right and non-far right voters

Note: A value of 0 indicates a low evaluation; a value of 10 indicates a high evaluation. Source: ESS 2002-2018

Next, our analyses illustrate first that those individuals who trust the domestic political institutions in their country and positively evaluate system performance and policy outputs are less likely to opt for a far-right party in a national election. As their approval of institutions improves, these individuals distance themselves from the far right. These are peripheral far-right voters, driven by discontent.

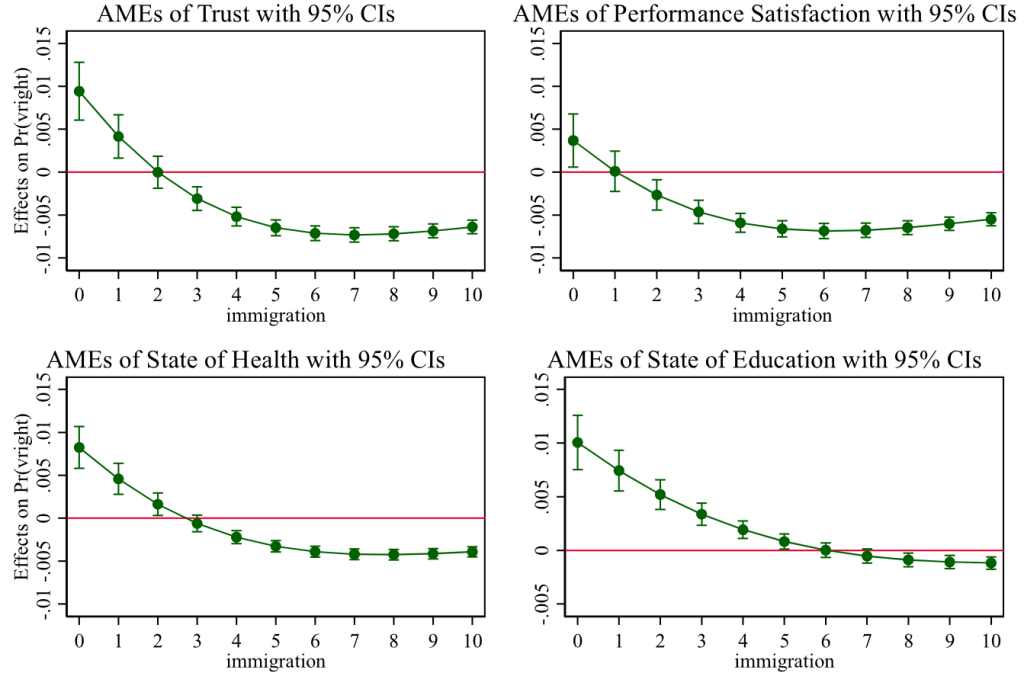

Second, evaluations of the democratic process are positively associated with far-right party support among some anti-immigrant voters. These are core far-right voters driven by nationalism (see Figure 2). For some nationalist voters, their likelihood to opt for the far right increases as evaluations of the democratic process improve, revealing a potentially galvanising effect among some anti-immigrant voters.

Figure 2: Average marginal effects of evaluations of the democratic process conditional on immigration attitudes

Note: Immigration: 0 = anti-immigrant; 10 = pro-immigrant. Estimates from multilevel logistic random-intercept models. Source: ESS 2002 to 2018

In sum, there is no typical far-right voter. We show this by focusing on political trust and system performance: when the broad framework of collective cooperation is perceived to be working well, citizens are indeed less likely to resort to the far right. But for those core far-right supporters with extreme views on immigration, the mechanism is different. Whereas positive evaluations of the democratic process make it unlikely for the far right to expand its appeal, they may intensify support among some segments of its core electorate.

One of the main implications of this finding is that research focusing on these various dimensions of populism and democratic politics, especially in an era of sustained levels of distrust and the simultaneous rise of populism in Europe and beyond, should pay more attention to intra-partisan voter heterogeneity. This is significant as it highlights the multifaceted nature of the far-right populist appeal to voters with different preferences and incentives.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of European Public Policy.