The judges at the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) are among Europe’s most powerful political figures. When judges are nominated for renewal by their member states, an independent panel evaluates their job performance, and their productivity is one of the key performance indicators. But how should the panel assess their productivity? Which judges are the best and worst performers? Drawing on a new dataset, Josh Fjelstul and Matt Gabel evaluate the productivity of all current CJEU judges, accounting for relevant case characteristics. They find the current process is likely biased against judges who hear more complex cases.

The judges at the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) are among Europe’s most powerful political figures. CJEU judges decide hundreds of cases a year that define and enforce the rights of hundreds of millions of EU citizens and shape the rules of the world’s second largest economy. It matters which judges get appointed to Europe’s highest court – and how effective they are at their jobs.

When a member state nominates a sitting CJEU judge for another term, an independent body – called the Article 255 panel – evaluates their job performance. The panel’s recommendation is non-binding but carries substantial weight. How should the panel evaluate job performance?

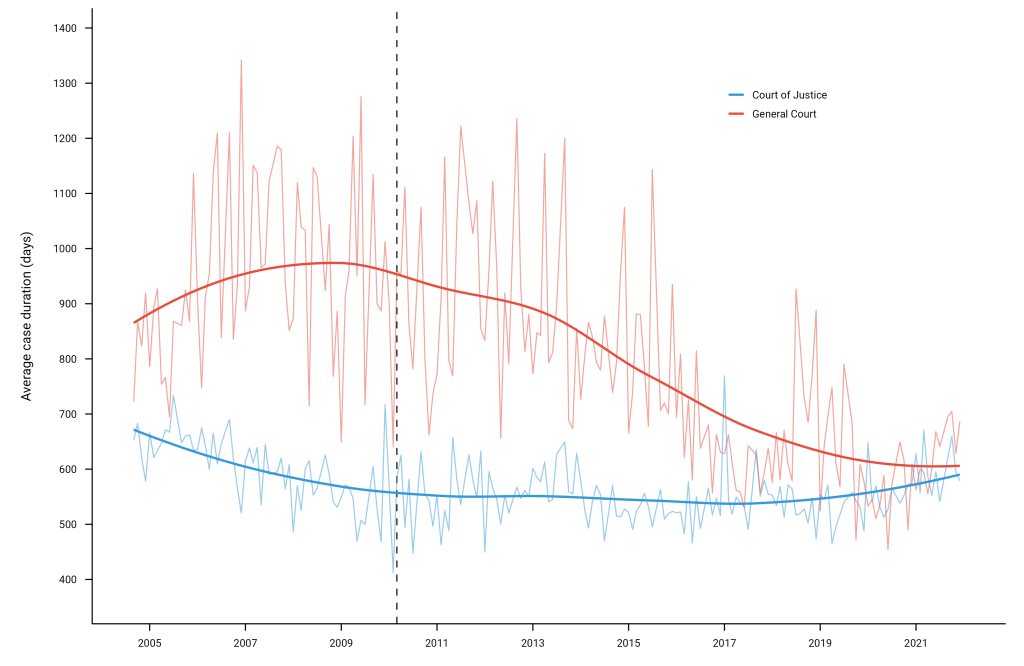

One of the main performance indicators that the Article 255 panel emphasises is productivity – how quickly the court decides the cases that a judge is responsible for managing. This makes sense. The CJEU has a huge backlog of cases, and long delays – cases currently take an average of 17 months to decide – undermine the timely administration of justice in the EU. Figure 1 shows average case duration since 2004.

Figure 1: Average case duration over time in the Court of Justice of the European Union

Note: This figure shows the average duration of Court of Justice and General Court cases by month since 2004.

By emphasising productivity, the Article 255 panel hopes to incentivise and reward CJEU judges for concluding cases more quickly. But fairly measuring and comparing productivity is hard. The panel recognises this and takes into account some case characteristics that influence duration when evaluating productivity. It’s not clear, however, exactly how the panel does this or how much it matters.

We propose a systematic method for controlling for case characteristics and demonstrate its impact on estimating the relative productivity of judges. The panel’s list of relevant case characteristics is a good starting point, but it’s incomplete. We show that the panel should also consider the complexity of cases in making comparisons of productivity. Simply put, some cases are more complex than others, and should therefore take longer.

Using new data on every CJEU judgment (2004-2022), we create a productivity index based on a statistical model that controls for case characteristics identified by the panel and for measures of case complexity. We rank-order all CJEU judges active since 2004 based on their average case duration and our productivity index. When we account for a more comprehensive set of case characteristics, we get a substantially different rank-ordering at both courts. This shows how important it is for the Article 255 panel to account for case characteristics when evaluating the productivity of judges who are up for reappointment.

How does the EU evaluate the performance of CJEU judges?

The Article 255 panel writes explicitly in its annual reports about the criteria they use to evaluate CJEU judges for reappointment. The panel is interested in “a more analytical approach to assessing the candidates’ productivity” that controls for factors that affect case duration.

The panel asks all judges up for reappointment to the Court of Justice and the General Court to provide a list of cases for which they were the Judge-Rapporteur (the judge who manages the case) and to indicate (a) the formation of the Court and (b) the subject matter of the case. The panel then compares the average duration of cases for each judge across similar cases based on these factors. But we don’t know exactly how the Article 255 panel does this – either how they measure these factors or how they adjust for them in assessing productivity. We propose and evaluate a method that fits the bill.

A new productivity index for CJEU judges

The simplest way to measure judge productivity is to calculate the average duration of all cases assigned to each Judge-Rapporteur. This is a useful baseline that’s consistent with the information the panel solicits from the nominees. But to meet the panel’s stated goals, that productivity measure should adjust for relevant case characteristics that influence duration and that likely vary across judges.

We develop a productivity index that does this. We start by estimating a separate statistical model for each court that predicts case duration (see our GitHub repository for details) based on the identity of the Judge-Rapporteur, controlling for case characteristics. Our model allows us to estimate the productivity of each judge relative to the president of each court, who serves as the baseline.

We control for measurable case characteristics that we expect to be correlated with the identity of the Judge-Rapporteur and with case duration. We include variables that capture the procedural, legal, and policy complexity of CJEU cases. All of the data for our analysis comes from the new IUROPA CJEU Database, published by The IUROPA Project. This database includes comprehensive information on all CJEU judgments, cases, and judges.

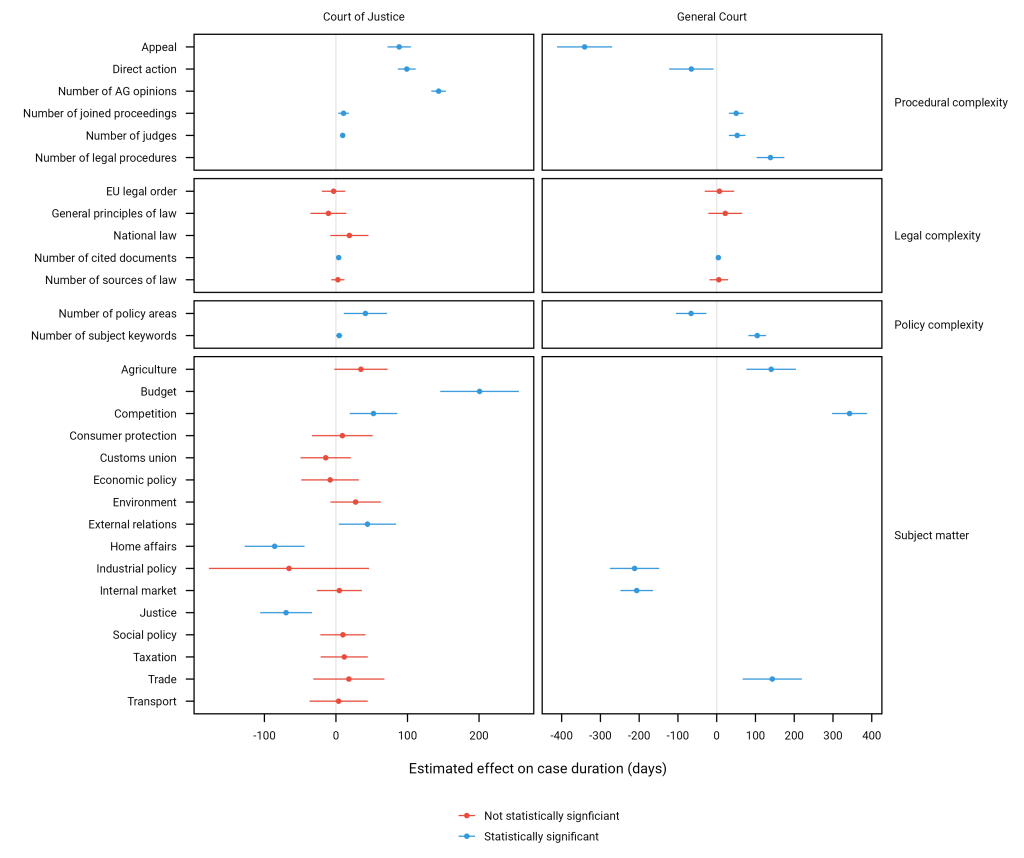

Figure 2 shows the estimated effect of a one-unit increase in each of these variables on case duration. As the panel expects, the formation of the court (the number of judges) and the subject matter systematically affect duration. But the list of relevant factors goes well beyond that. We show that a comprehensive adjustment for case characteristics that influence duration should also include measures of case complexity.

Figure 2: Estimated marginal effects

Note: This figure shows the average marginal effects of the variables in our statistical model (excluding Judge-Rapporteur fixed effects).

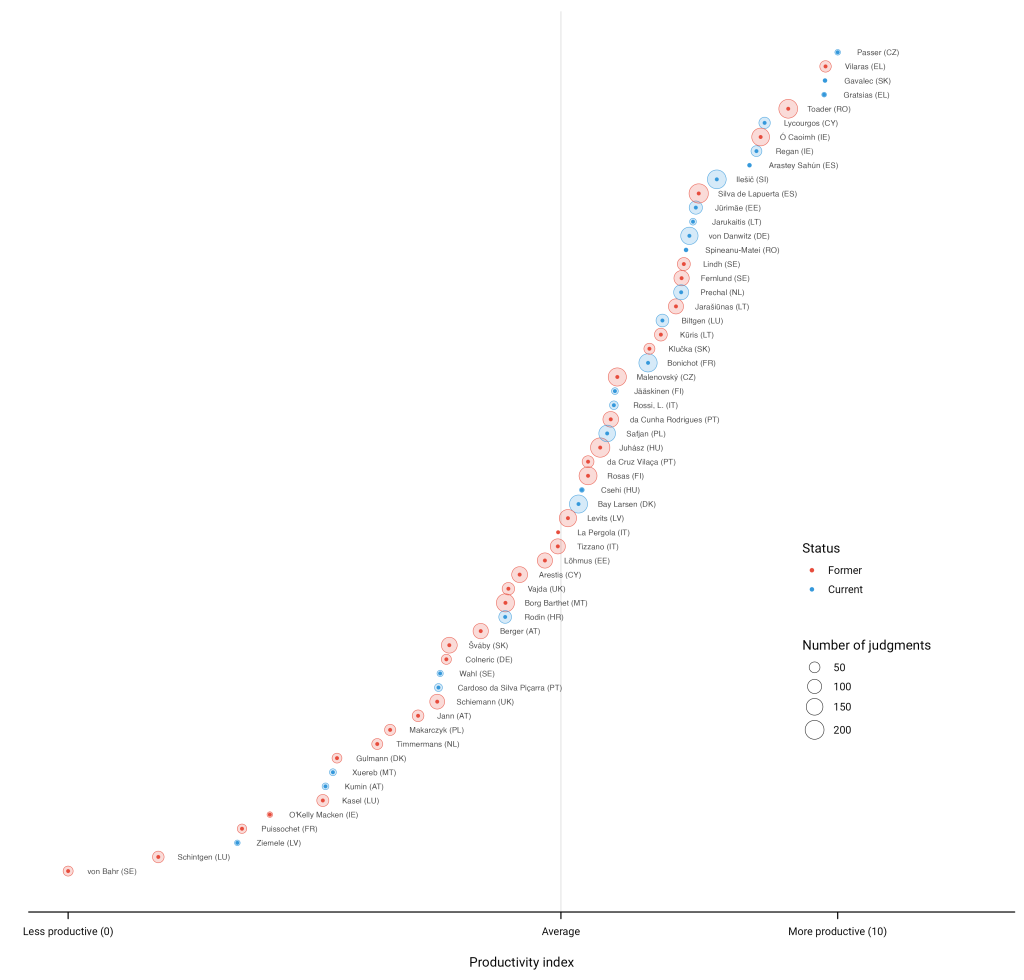

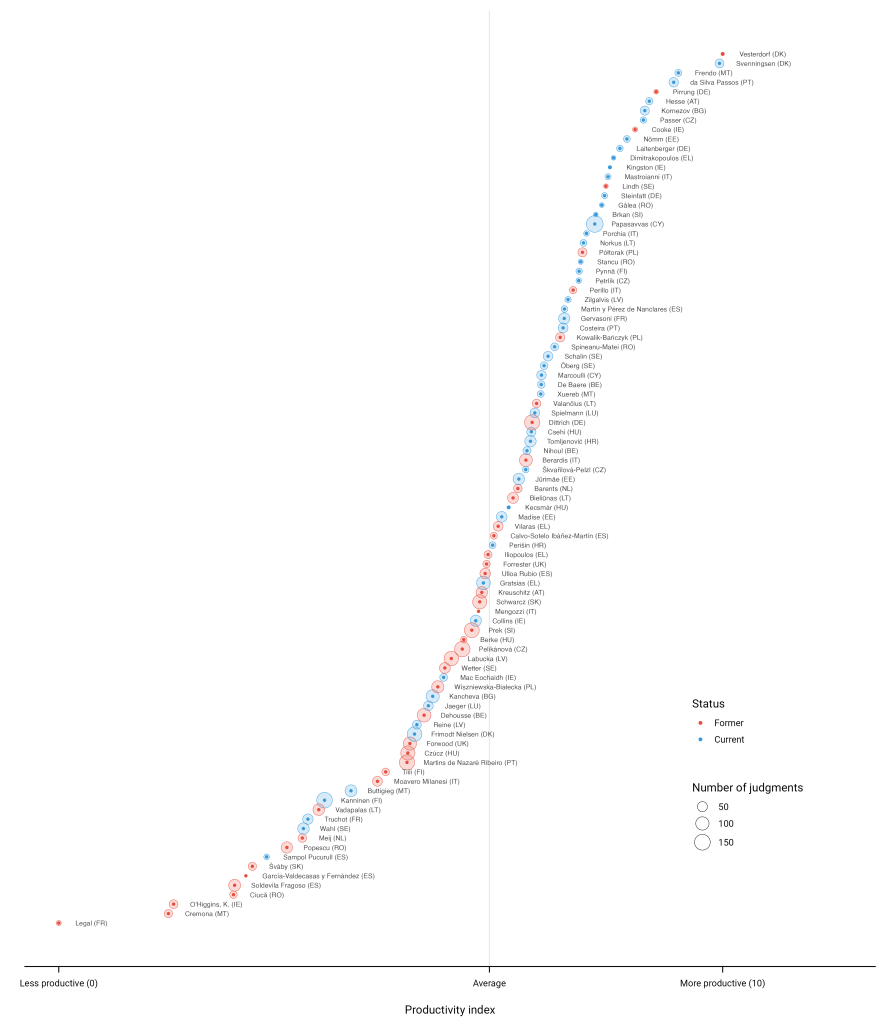

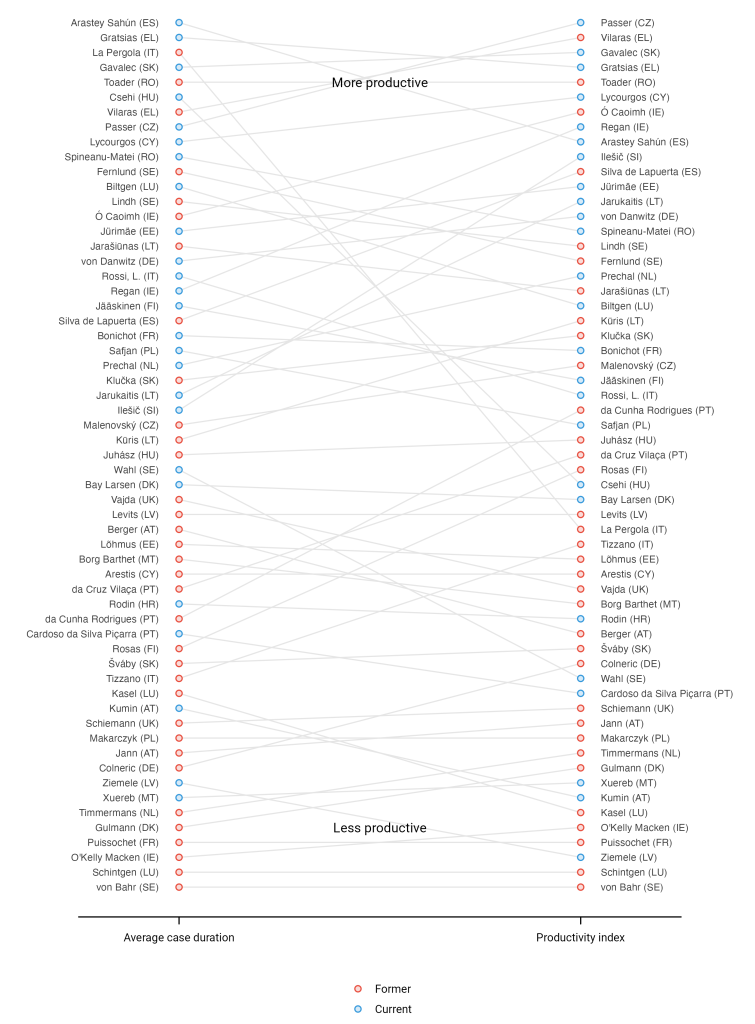

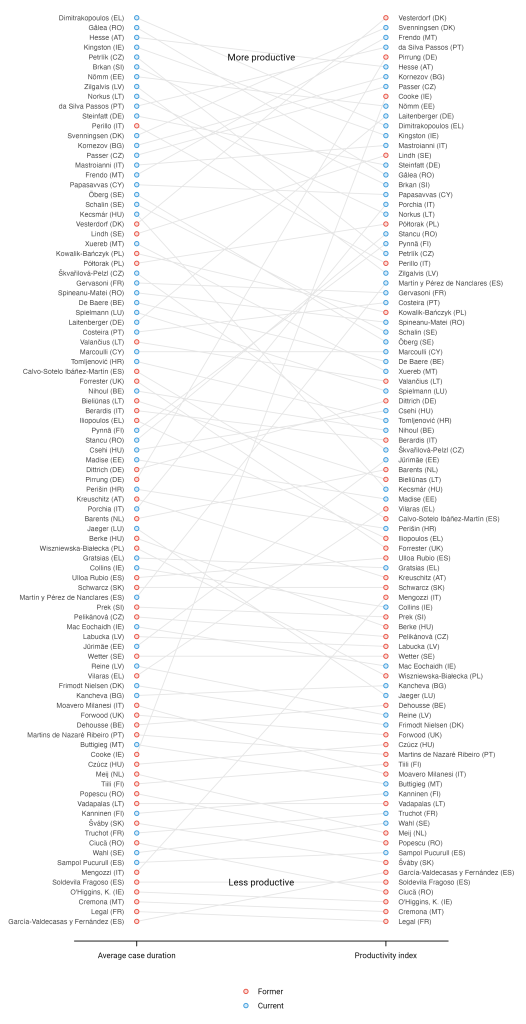

We use the estimates from our model to create an index that ranges from 0 to 10, where 0 indicates the least productive judge on each court and 10 indicates the most productive judge. Figures 3 and 4 show how judges at the Court of Justice and the General Court rank based on our productivity index. Judges who have higher values are more productive, controlling for case characteristics.

Figure 3: Estimated productivity of judges at the Court of Justice (2004-2022)

Note: This figure shows the estimated productivity index for all current and former Court of Justice judges active since 2004.

Figure 4: Estimated productivity of judges at the General Court (2004-2022)

Note: This figure shows the estimated productivity index for all current and former General Court judges active since 2004.

Figures 5 and 6 show judges ranked by average case duration (on the left) compared to the same judges ranked by our productivity index (on the right) for both courts. Judges who are higher in the rankings are more productive. Judges with lines that slope up are underrated when we don’t account for case characteristics and judges with lines that slope down are overrated.

Figure 5: Court of Justice judges ranked by average case duration and productivity index (2004-2022)

Note: This figure compares average case duration and our productivity index for all Court of Justice judges active since 2004.

Figure 6: General Court judges ranked by average case duration and productivity index (2004-2022)

Note: This figure compares average case duration and our productivity index for all General Court judges active since 2004.

In many cases, a judge’s rank changes by double digits. Accounting for case characteristics clearly changes the picture at both courts.

Our recommendation to the Article 255 panel

The Article 255 panel evaluates the productivity of CJEU judges up for reappointment, but it doesn’t fully take into account the fact that some judges’ cases are more complex – and should therefore take longer. We create a productivity index that better isolates each judges’ impact on case duration, and we show that the rank-ordering of judges changes significantly when we account for the complexity of the cases that each judge is responsible for.

We recommend that the panel use a measure of productivity that accounts for case complexity. Otherwise, judges that handle more complex cases are likely to be underrated in terms of their productivity and judges that handle simpler cases are likely to be overrated. Our method addresses this bias. It’s more systematic, more accurate, and fairer.