The EU responded to the Eurozone crisis by recommitting to the Stability and Growth Pact – the Eurozone’s legal limit on the size of member states’ deficits and debts. But when do EU citizens support enforcement of these limits, and do patterns in public opinion make enforcement more or less likely? Drawing on new research, Joshua Fjelstul explains how EU citizens evaluate the policy of enforcement through the lens of their political commitment to the euro, and how patterns in public support make enforcement less likely.

The Eurozone crisis threatened the future of the EU’s crowning economic achievement – the euro. After adopting the euro, and gaining access to cheaper credit, many Eurozone member states over-spent and over-borrowed, violating the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) criteria – the Eurozone’s legal limits on the size of member states’ deficits (3 percent of GDP) and debts (60 percent of GDP).

Yet, the Council and the Commission, jointly tasked by the EU treaties with enforcing the Eurozone’s rules, failed to enforce the SGP criteria. Many member states, including Greece, racked up unsustainable debts, setting the stage for the Eurozone crisis to break out in 2009. The EU responded to the crisis by reforming and strengthening the Stability and Growth Pact, and recommitting to enforcing the criteria. The Commission can now more effectively pre-screen member states’ budgets and more easily impose financial sanctions on member states for violating the rules.

But when are EU citizens more likely to support enforcement of the rules in the Stability and Growth Pact as a response to the Eurozone crisis, and do patterns in public support for enforcement make enforcement more or less likely? In a new study, I argue that EU citizens evaluate the economic and political consequences of enforcement through the lens of their political commitment to the euro, and that patterns in public support could undermine enforcement.

Using a Bayesian statistical analysis of Eurobarometer survey data from 2013, I show that respondents’ support for SGP enforcement depends not only on their member state’s compliance with the criteria, which shapes the economic and political consequences of enforcement, but also on their political support for the euro, which shapes how they interpret those consequences.

The Stability and Growth Pact

The stability of the Eurozone depends on a non-credible promise: that member states will refrain from over-spending and over-borrowing to boost short-term economic growth. Politicians have strong political incentives to over-spend to maximise their re-election chances.

If investors start to doubt whether a member state can meet its short-term financial obligations, they could launch a speculative attack on the member state’s sovereign bonds. As the Greek crisis demonstrated in 2009, a speculative attack can cause financial contagion, spreading the crisis to other Eurozone members. Tied together by the euro, individual Eurozone members can’t use standard monetary policy tools to respond to a crisis.

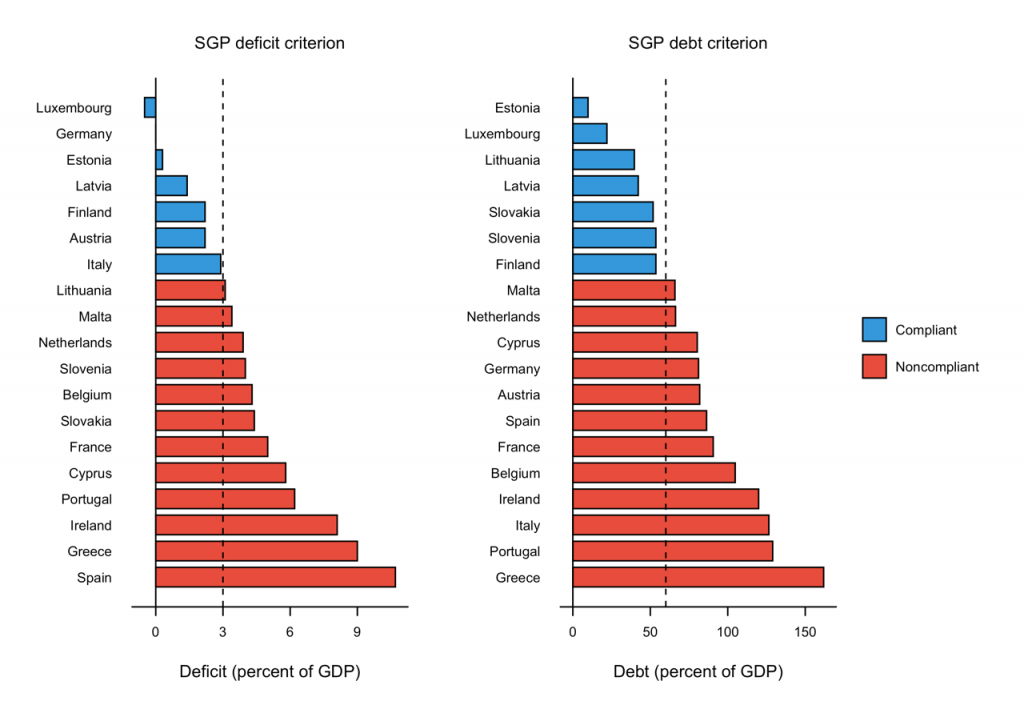

By putting limits on member states’ deficits and debts, the Stability and Growth Pact can reduce the risk of a debt crisis. But this only works if the EU actually enforces these limits. In the 2000s, the Council and the Commission failed to enforce the rules, despite clear violations. Figure 1 shows member state compliance with the criteria in 2012: only a handful of Eurozone member states were following the rules.

Figure 1: Compliance with the Stability and Growth Pact criteria

Note: This figure shows member state noncompliance with the SGP deficit criteria (left) and the SGP debt criteria (right) in 2012. The data is from Eurostat.

The economic and political consequences of SGP enforcement depend on a member state’s noncompliance with the criteria. EU citizens weigh these consequences when evaluating the policy of enforcement.

Noncompliance with the debt criterion increases the risk of a debt crisis, which could destabilise the Eurozone and force crisis-hit member states, facing a risk of sovereign default, to exit the Eurozone. Leaving the Eurozone would allow a debt-burdened member state to reintroduce and depreciate its pre-euro currency, reducing the real value of its debt. But the short-term economic turmoil caused by leaving the Eurozone could cause significant political and social upheaval.

Noncompliance with the deficit criterion increases the risk of SGP enforcement in the form of EU-imposed austerity. By reducing a member state’s deficit, austerity measures reassure investors and reduces the risk of a speculative attack. The downside of austerity is that it hurts economic growth. Recent research finds that raising taxes hurts more than cutting spending, but that both are bad for growth in the short term.

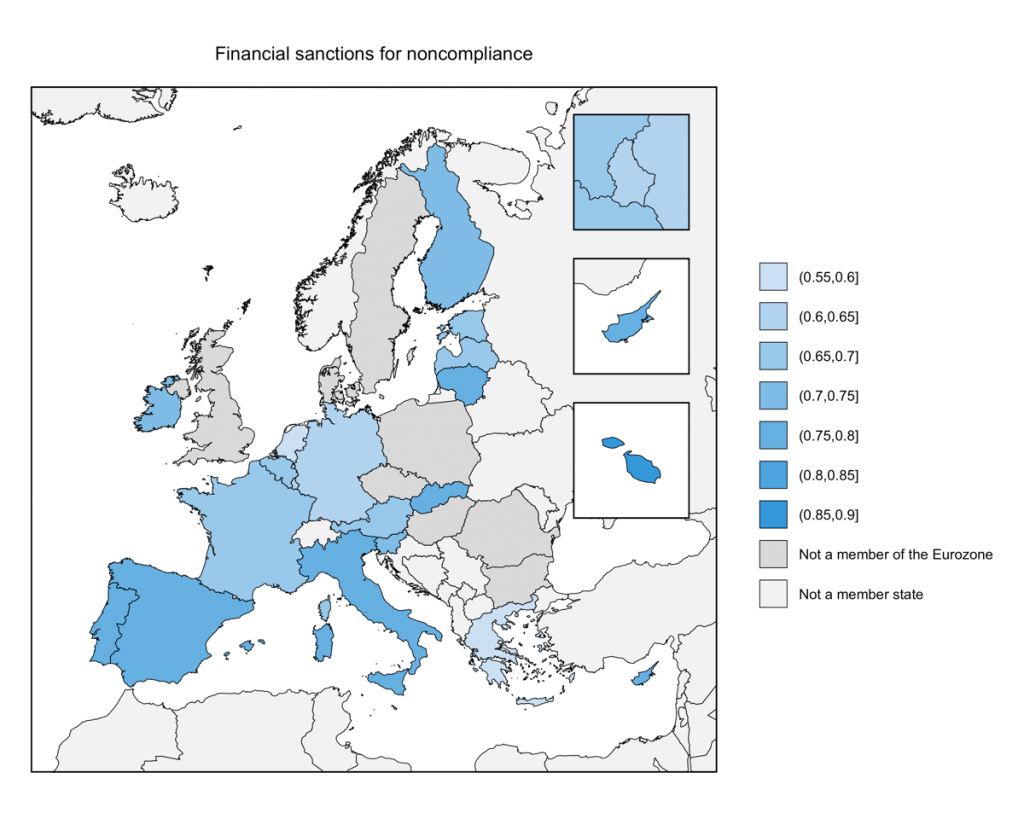

There are two mechanisms through which the EU can enforce the Stability and Growth Pact and incentivise austerity, one preemptive, the other reactionary. First, the EU can pre-approve member states’ budgets, which could prevent over-spending before it occurs. Second, the EU can impose financial sanctions for over-spending, which could incentivise fiscal discipline. Figures 2 and 3 show the percentage of respondents who think each mechanism is an effective response to the Eurozone crisis.

Figure 2: Public support for pre-approval of member states’ budgets

Note: This figure shows the percentage of respondents in each Eurozone member state (plus Latvia and Lithuania) who think pre-approval of member states’ budgets is an effective solution to the Eurozone crisis. The data is from the 2013 Standard Eurobarometer surveys (waves 79 and 80).

Figure 3: Public support for financial sanctions for noncompliance

Note: This figure shows the percentage of respondents in each Eurozone member state (plus Latvia and Lithuania) who think financial sanctions for noncompliance are an effective solution to the Eurozone crisis. The data is from the 2013 Standard Eurobarometer surveys (waves 79 and 80).

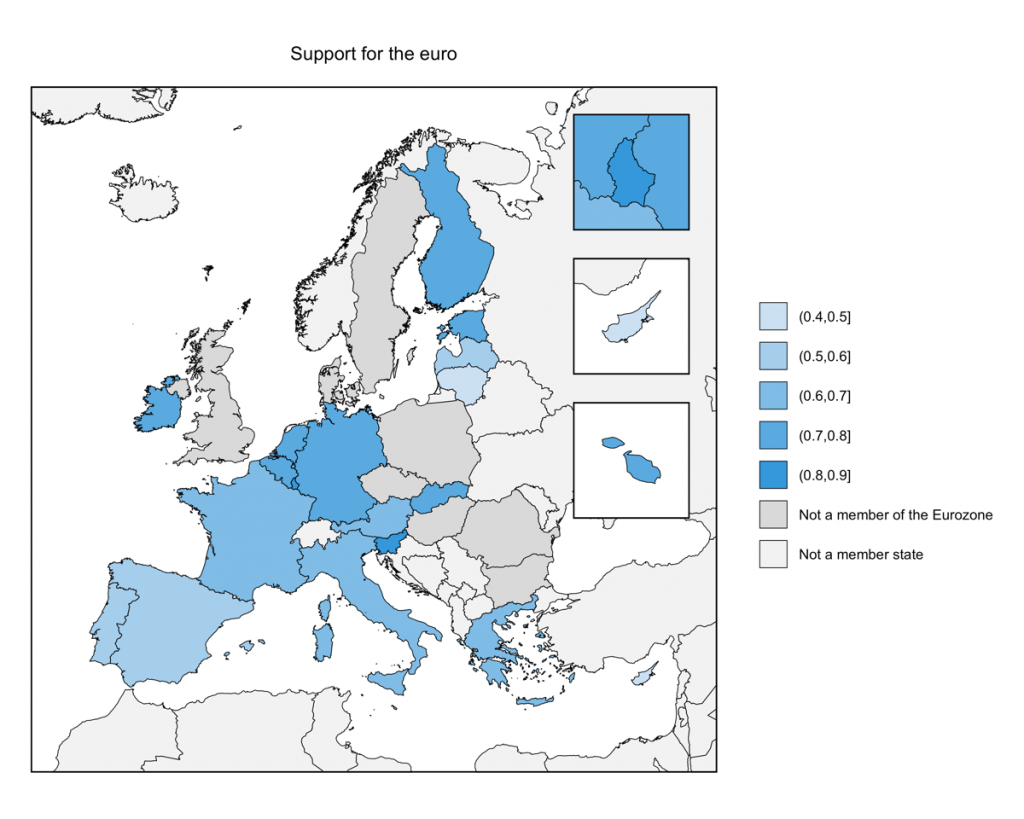

The consequences of SGP enforcement shape public opinion, but EU citizens evaluate these consequences through the lens of their political commitment to the euro. Figure 4 shows the percentage of respondents in each member state who support the euro.

Figure 4: Public support for the euro

Note: This figure shows the percentage of respondents in each Eurozone member state (plus Latvia and Lithuania) who support the euro. The data is from the 2013 Standard Eurobarometer surveys (waves 79 and 80).

Euro-supporters tend to be more supportive of SGP enforcement than euro-opponents. For euro-supporters, enforcement resolves the crisis in a way that enhances the stability of the Eurozone and the viability of the euro as a political project. However, even euro-supporters are less likely to support enforcement when it would lead to EU-imposed austerity for their member state.

Euro-opponents tend to be less supportive of SGP enforcement because they would prefer to resolve the crisis by reverting back to the pre-Eurozone era of national currencies, when member states had greater fiscal and monetary freedom. Euro-opponents see the euro as part of the problem – a source of financial contagion and a constraint on monetary policy. They would rather reduce the risk of financial contagion by dissolving the Eurozone than by enforcing the Stability and Growth Pact to constrain spending.

Implications for enforcement

In addition to explaining how EU citizens evaluate the EU’s policy response to the Eurozone crisis, I find that patterns in public support could undermine EU enforcement of the Stability and Growth Pact. Recent research suggests that the Commission is less likely to enforce EU law when compliance is more costly, such as when there is less support for enforcement. Support for SGP enforcement is generally lower when a member state is violating the criteria, which is precisely when enforcement is most important for preventing a crisis. This raises questions about whether the EU can prevent another crisis.

The lesson for EU policy-makers is that it’s important to consider how the public will react to a policy and whether a lack of public buy-in could undermine the EU’s political will to enforce it. As we can see from the EU’s failure to enforce the SGP criteria in the lead-up to the Eurozone crisis and from the Commission’s tepid response to the ongoing rule of law crisis with Poland and Hungary, there’s no guarantee the EU will enforce EU law. Absent a fiscal union, the future stability of the euro depends on the EU actually enforcing the reformed Stability and Growth Pact, even in the face of public opposition.