Severe Housing Deprivation is the European Union’s primary indicator for monitoring housing quality problems. But as Rod Hick, Marco Pomati and Mark Stephens argue, issues with the statistical performance of this measure mean it should be rethought.

Monitoring the extent of housing quality problems presents a real challenge. We typically monitor population living standards through statistics derived from social surveys, yet the sampling frames of such surveys exclude many of the very people who might be said to be suffering the most extreme forms of unmet shelter need, such as those experiencing rooflessness, living in various forms of supported housing, or living in caravans. But even for the population living in private households there is little agreement about how ‘housing deprivation’ should be understood.

One prominent measure of housing inadequacy is the EU’s official Severe Housing Deprivation measure. The EU’s statistical agency Eurostat monitors the prevalence of a number of problems with housing conditions – the percentage of individuals living in households with a leaking roof, with no bath and shower and no indoor toilet, or in a dwelling considered too dark. Eurostat’s Severe Housing Deprivation measure reflects when households experience at least one of these deprivations in housing conditions and overcrowding.

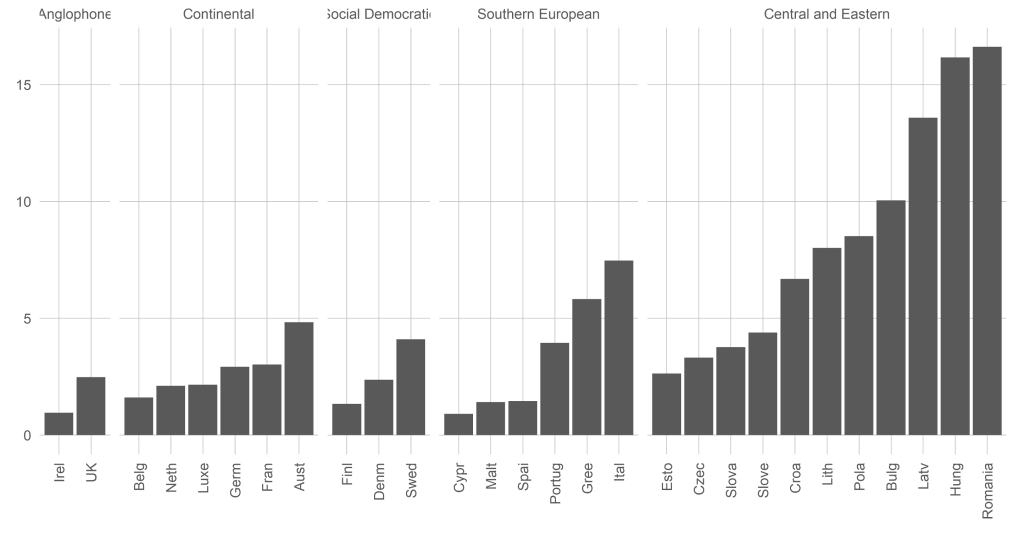

In most European nations, only a small proportion of households experience Severe Housing Deprivation, with rates below 3% in about half of the EU’s member states (and the UK).Rates are especially low in Ireland, Cyprus, Finland and Malta and are highest in some Central and Eastern European nations.

Figure 1: Severe housing deprivation by country (2016)

Source: Hick, Pomati and Stephens (2022)

This appears to suggest that housing quality problems are marginal in many nations. However, our research shows that the two components of the Severe Housing Deprivation construct – overcrowding and housing conditions problems – are very weakly related. These are problems experienced by quite different households. One consequence is that the incidence of either of these problems individually is substantially greater than for the joint experience of both problems.

To take just one example: across the continent, nearly one in five (19%) of households headed by someone aged 50 to 64 experienced problems with housing conditions (a household that has a leaking roof, no indoor toilet, or is too dark, as mentioned above), but just 3% of this group experienced Severe Housing Deprivation. The focus on households experiencing both problems with housing conditions and overcrowding substantially alters our understanding of the extent of housing deprivation problems in Europe.

The issues with this are not limited to the technicalities or measurement, because the two problems appear to respond to quite different determinants. Overcrowding is strongly related to GDP per capita: its incidence is thus much greater in Central and Eastern Europe than it is in the Anglophone and Scandinavian nations. By contrast, the deprivation of housing conditions is much more closely related to levels of relative income poverty and has a very different distribution across Europe. Thus, whether we combine the two housing deprivation components or analyse them separately not only gives us a very different picture about the extent of the challenge we face, but potentially leads to quite different accounts of how to go about tackling these problems.

Getting the measurement of housing deprivation right is therefore crucial, and rethinking this measure requires a two-step process. The first concerns the selection of items themselves: are these indicators – a leaking roof, an indoor toilet, not having enough natural light, overcrowding – the right ones?

Is the basis on which they are collected – e.g. self-reported circumstances in the case of the housing conditions items and objective assessments in the case of overcrowding – as we would choose? And are the thresholds used to determine overcrowding meaningful? This is a potentially far-reaching reconsideration and while it may lead to improved measurement, there is undoubtedly a balance to be struck between optimising the indicators themselves and the advantages to be gained by consistency in measurement through time.

The second step addresses the question of whether, and potentially how, these items should be aggregated. The evidence here speaks clearly: problems with housing conditions and overcrowding are very different issues, affecting very different households. There is little statistical reason to focus only on households who experience both of these problems jointly. Such a reason can only therefore be political, but we lack an explicit argument for this limited focus. Absent a compelling reason for only focusing on the intersection, and given their weak empirical relationship, there would appear to be a strong case for considering these items separately.

This implies a substantial undertaking but revising the measurement of housing deprivation would not only give us a better understanding of the scale and distribution of housing quality problems in Europe – a more robust monitoring tool would also provide a better guide to policymakers in responding to the problem of inadequate housing.