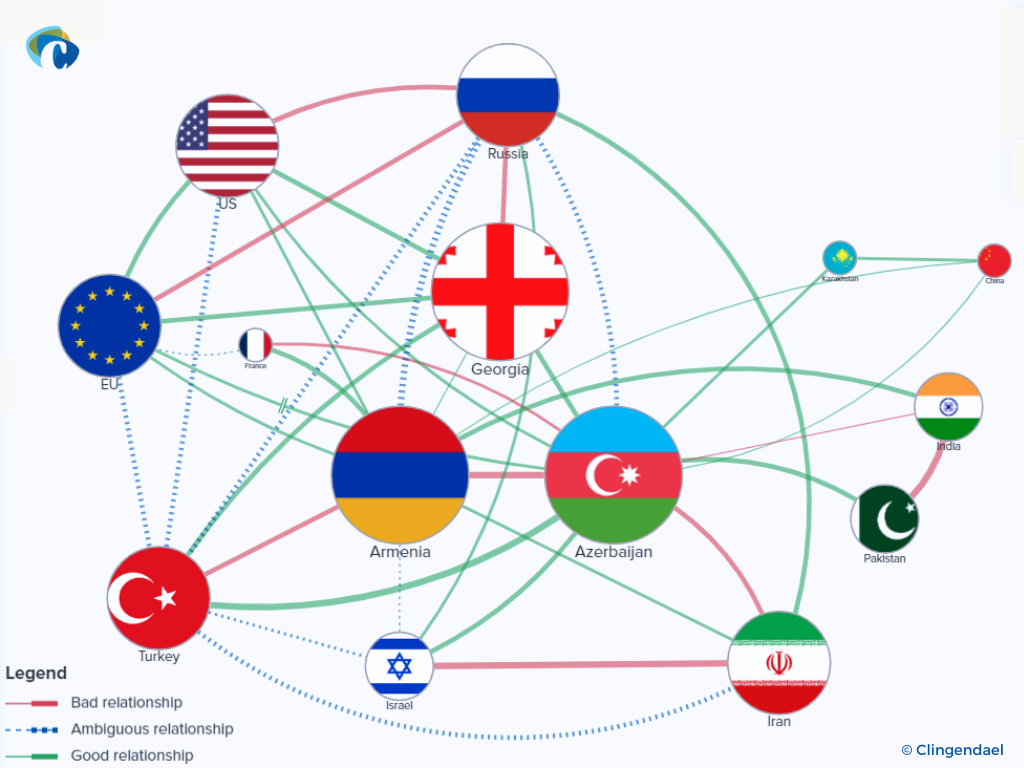

The tectonic plates of geopolitics are shifting in such a profound way that has not been seen since the end of the Cold War. The Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 has not only increased tensions between the world’s major powers, but also severely impacted the regions in which they traditionally strive to project their power. This applies especially to areas in the wider Eurasian region that the Russian Federation unjustifiably considers as part of its sphere of influence, such as the South Caucasus. Russia’s failure to achieve a quick and decisive victory in its full-scale invasion of Ukraine has not only forced the Kremlin to limit its objectives on the battlefield, at least for the time being, to Ukraine’s east. It has also reduced the credibility of the Russian military that much of its power projection has depended upon – and has reduced its attractiveness as a security partner for countries that have traditionally regarded Russia as such. Russia has had to withdraw some of its troops and military equipment from the South Caucasus, its leadership is preoccupied with Ukraine, and it has not lived up to its security commitments to Armenia. This has contributed to a geopolitical vacuum and uncertainty in the South Caucasus that other actors are eager to exploit.

While both Russia and much of the rest of the world were focusing predominantly on Ukraine, in the meanwhile violence has once again flared up between Armenia and Azerbaijan and the situation both on the military and on the diplomatic fronts is changing rapidly. Both the US and the EU have made attempts to increase their leverage in the region at Russia’s expense. Most notably the US sent its Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi to Armenia in September 2022, in the highest-level visit by a US official since Armenia’s independence, in order to project US support. The EU has tried to seize the initiative as a facilitator and mediator between Yerevan and Baku and has sent an EU Mission to Armenia, first as a temporary monitoring capacity in October 2022 and in January 2023 with a dedicated field operation despite Azerbaijani objections. In Georgia, where the EU has had such a field presence since 2008 and has mediated in the protracted conflicts over Abkhazia and South Ossetia, it has also recently taken a central role in mediating between the different factions that are dominating Georgia’s polarised political landscape, using Georgia’s newly obtained status as a potential EU candidate country as political leverage.

Access the full publication here

About the Authors