Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 generated an unprecedented energy crisis in the EU. Dimitar Lilkov writes that while the EU showed remarkable resilience in securing its energy supply during the peak of the crisis, it remains reliant on costly energy imports to meet growing demand. Decisive policies are needed to limit price volatility and ensure energy security within the EU.

Exactly a year ago, the EU was in the midst of the biggest energy crisis in its history. The Kremlin’s weaponisation of gas exports brought skyrocketing bills and threw the energy market into disarray. The day of reckoning had come for many European capitals who had underestimated the energy security risks stemming from over-dependence on Russian gas.

Fortunately, the EU managed to overcome the crisis through a combination of prudent policy measures, diversification of energy imports and considerable emergency spending. As the 2023-24 heating season begins, it is necessary to evaluate this monumental shift and consider the future perspectives for guaranteeing energy security and price stability in the EU.

Taking stock

If we compare today with the grim energy realities of last October, the EU is definitely in better shape. Average wholesale electricity prices per MWh are a fraction of their astronomic peak. Impressively, the EU managed to fill its gas storage facilities to 90% of capacity by the end of this summer. Additional volumes are even stored in Ukraine, which has offered its spare storage sites. All in all, European leaders and experts can look more optimistically on the upcoming winter.

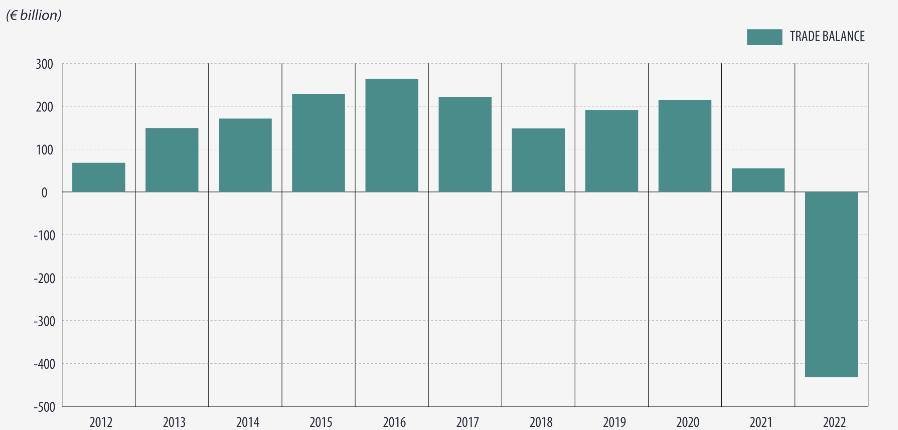

However, this success came at a price. The high energy costs put a serious strain on public budgets. The EU allocated and earmarked close to €700 billion in different state support measures to shield households and industry. These subsidies created their own ripple effect across the EU, as not every member state had the fiscal space to provide such support. The skyrocketing price of energy imports resulted in the highest ever EU trade deficit of €432 billion in 2022 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Extra EU trade in goods (2012-2022)

Source: Eurostat

Additionally, the EU-wide initiative to reduce overall gas consumption by at least 15% was achieved through much needed optimisation of energy usage but also by depriving energy intensive industry of required power. European steel, aluminium, cement, glass and fertiliser production registered a discernible drop with mounting fears about the long-term loss of manufacturing output and deindustrialisation in the EU.

Friends in need and LNG lifelines

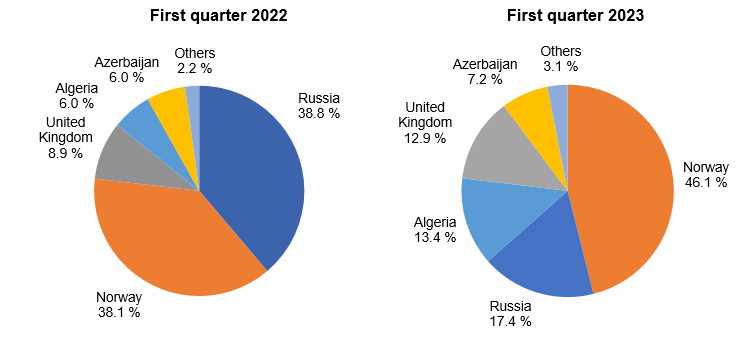

Replacing Russian gas deliveries in a matter of weeks was costly, but it was an achievement nonetheless. European countries demonstrated remarkable resilience in securing the required volumes. Two international allies were key in this endeavour. Norway guaranteed the stable flows of pipeline gas and even increased the supply to several European partners. Thanks to the country’s direct terminal connections with the continent, Norway piped more than 100 billion cubic metres (bcm) of natural gas to the EU and Britain. Unsurprisingly, Norway has raced past Russia and is currently the most important supplier of conventional pipeline gas to the EU (Figure 2).

Figure 2: EU imports of pipeline natural gas by partner

Source: Eurostat

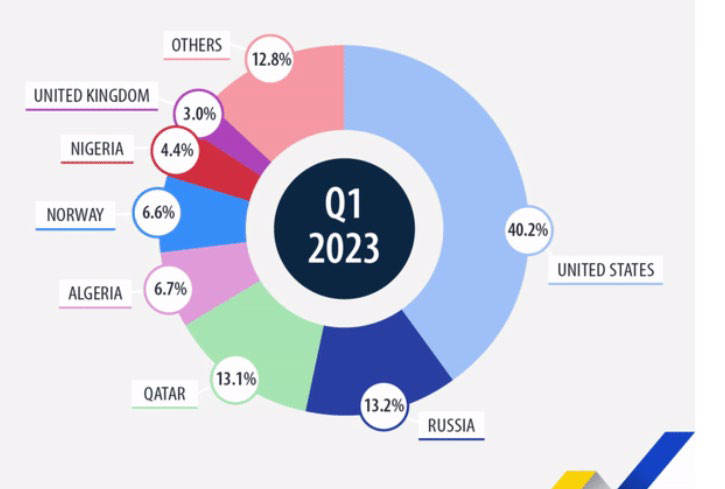

The second vital player is the United States. Conventional pipeline deliveries alone couldn’t meet European demand. The abundance of US liquefied natural gas (LNG) export volumes, coupled with a lack of destination clauses for many US export contracts, meant that cargo could be diverted from Asia to Europe. This coincided with an increase of investment in LNG terminals across the EU. Floating LNG infrastructure also played a role due to the flexibility in deployment and lower related costs.

All in all, the total share of LNG imports in Europe doubled compared to the volumes before Russia’s unprovoked war in Ukraine. The lion’s share of these deliveries came from the US, which supplied around 56 bcm in 2022, a substantial increase from the 22 bcm the year prior.

Figure 3: EU imports of LNG by partner

Source: Eurostat

This massive increase came as a result of a political pact between Brussels and Washington that pledged to ensure continuous US imports by 2030. This makes the US the biggest importer of LNG and a direct guarantor of Europe’s energy security (Figure 3). This grand transatlantic bargain was sealed by the EU-US task force on energy security, which confirms the long-term commitment of Washington, as well as future efforts to reduce methane emissions.

Europe’s Achilles’ heel

The EU managed to brave the energy storm, but the ship is still rickety. Energy prices in the EU remain extremely volatile and even the talk of strikes in distant Australian LNG production sites can instantly shoot spot prices up. The nervousness of investors, coupled with the crisis in Gaza, pushed the Dutch TTF price benchmark to an eight-month high. While bills have fallen drastically compared to the peak of the crisis, they are more than double what they were when compared to average rates five years ago.

The EU continues to depend on imports for 80% of its natural gas and 90% of its crude oil usage, which leaves it exposed to the whims of global markets. European businesses pay more than triple the energy prices in the US, not to mention China. Embarrassingly, several European countries still import Russian LNG, not because they prefer dealing with Gazprom or other Russian energy moguls, but because they need the volumes to stabilise their energy mix.

This massive energy import dependency has been a severe handicap for the EU, compared to other global economies. Ever since the shale boom of the late 2000s, the US has enjoyed an energy glut. The current EU-US energy bargain is vital but also means that European counterparts have had to pay lavishly on the spot market in order to secure their energy supply. There are political risks, too. After the upcoming presidential election, a more hawkish US administration with unfavourable views about the EU might use this dependency to pressure European capitals.

In parallel, China also remains a source of anxiety. In the last decade, China has doubled its usage of natural gas and will likely remain a large player on the LNG global market. Beijing’s recent interest in long-term delivery contracts could limit future availability for European countries. In a nutshell, the EU’s energy Achilles’ heel will remain a long-term source of tension and impediment to economic competitiveness. Unfortunately, energy insecurity could also dampen the EU’s climate ambitions.

There are no easy fixes in such a bind, but EU countries should focus on a number of key priorities. First, we need political clarity on the long-term role of natural gas. It will be a vital transitory resource during the phasing out of coal and serve as an important back-up to cover for the intermittency of solar and wind output. European stakeholders must overcome their hesitancy to commit to beneficial deals due to concerns about the EU`s climate agenda. European homes and businesses will need reliable energy supply and natural gas will have a role in any viable decarbonisation scenario for the EU.

The EU’s LNG demand is projected to gravitate above 100 bcm per annum well into the 2030s and beyond. Given the structural shift to LNG imports, European countries should start committing to long-term LNG deals with a variety of providers, rather than pay top price on uncertain spot markets. Germany and France’s recent deals with Qatar are an important step in this direction.

Second, the EU should pursue all available avenues for diversifying its supply from reliable partners. The transatlantic deal on LNG is an important foundation but the next few years will be vital for expanding the energy mix. The EU’s traditional pipeline imports from non-Russian sources should be bolstered where possible.

Third, the EU should avoid overlooking its own potential for domestic output within the Black Sea, North Sea and the Mediterranean. After the phase-out of the Groningen gas fields, the EU’s native gas supply will become extremely low. EU member states need to collaborate to explore joint sites and ramp up the EU’s domestic production, which will play a key role as a transitory resource in Europe’s efforts to pursue decarbonisation and balance its energy mix.

Lastly, European countries should bolster their efforts to protect critical energy infrastructure. The damage suffered by the infamous Nord Stream 2 pipeline in 2022 was followed by suspected sabotage of the Baltic-connector pipeline. Such deliberate acts can cause major disruptions and bring severe hardship. It is welcome that NATO allies have already affirmed their commitment to respond if such an act was deliberate. A brutal war is being waged on the EU’s doorstep and European leaders must ensure the integrity of its citizens, assets and critical infrastructure.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Kodda/Shutterstock.com