Following her party’s victory in the Italian general election, Giorgia Meloni is set to lead Italy’s next government. Marina Cino Pagliarello and Davide Tedesco assess what her policy agenda might mean for both Italy and Europe.

The victory of Giorgia Meloni and the Brothers of Italy in the Italian general election would have seemed unthinkable only a few years ago. At the last general election in 2018, the party secured just 4% of the vote.

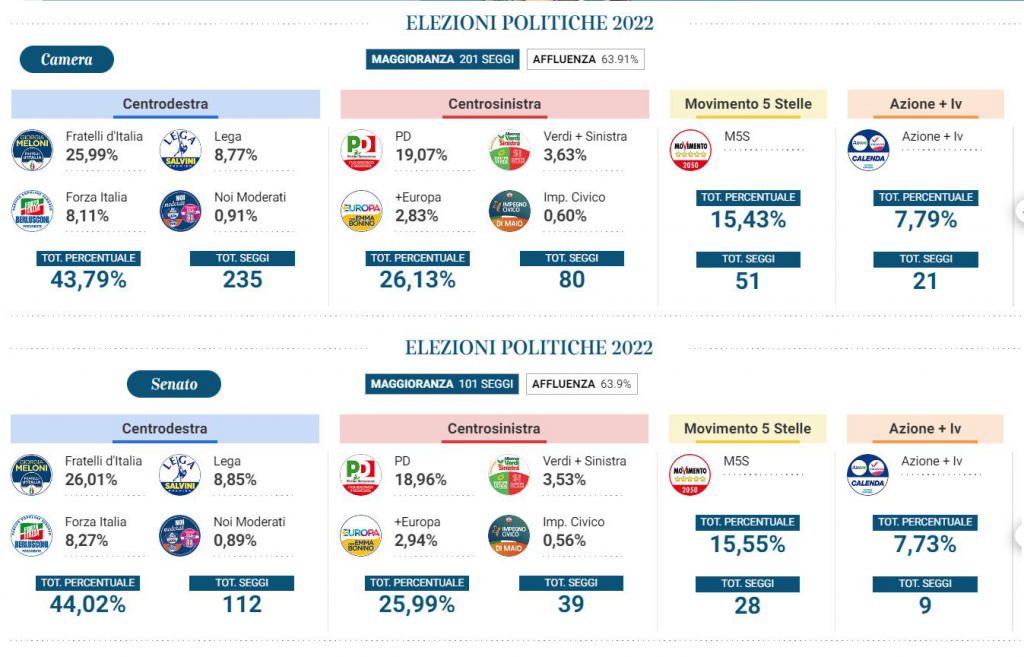

Yet, after the resignation of Mario Draghi on 21 July and a month of summer campaigning, Meloni’s party is, together with Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia and Matteo Salvini’s League, now the main political force in Italy. The right-wing coalition secured around 44% of the vote in total, winning a majority in both chambers, the Camera and Senato (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Italian general election result

Source: Ministry of the Interior

The election was not only important for Italy. Countries across the world watched with interest to determine whether the Brothers of Italy pose a threat to Italian democracy and whether their victory may lead to a populist resurgence in Europe. Meloni now has a clear majority to govern, though not the required majority to change the Italian Constitution. However, winning an election is not governing, and Italy’s new prime minister will face a series of difficult challenges over the coming months.

Italy’s first female leader

One of the key unknowns is which of the many faces of Giorgia Meloni will come to the fore in office. Will we see the Meloni who has become a champion of the far-right and a prominent defender of Viktor Orban? Or will it be the pragmatic Meloni who supported Mario Draghi’s response to the war in Ukraine that takes centre-stage as prime minister?

Meloni’s party traces its roots to the National Alliance and the post-fascist Italian Social Movement. It has often adopted an ambiguous position towards fascism, including sharing one of its key symbols (the tricolour flame) and praising Benito Mussolini’s leadership. It might be expected given this legacy that Meloni will pursue more restrictions on civil rights, more robust anti-immigration policies, and a change to the constitution to make the Italian president directly elected by voters. In this sense, the Brothers of Italy would align with the positions of Matteo Salvini’s League.

On the other hand, while Meloni will govern a largely Eurosceptic and anti-immigration coalition, she is also a capable politician with a view for what works electorally. She has demonstrated this in her carefully crafted charismatic and persistent public image as a ‘mother’, ‘Christian’, and a ‘national patriot’.

Recently, she has presented herself as a mainstream conservative in reassuring international markets and supporting the supply of weapons to Ukraine, in contrast to Salvini and Berlusconi, who have a history of articulating more pro-Putin stances. It remains to be seen whether Meloni will embrace this sense of pragmatism as prime minister, abandoning her more extreme far-right positions and establishing an entente cordiale with the EU to find common solutions to shared problems, such as the Ukraine crisis and Europe’s post-pandemic recovery.

Learning on the job

One of the most significant obstacles for Meloni will be to overcome her lack of experience in government. She has spent her entire career in opposition and will undoubtedly find it challenging to adapt to the new pressures of holding office.

While Berlusconi and Salvini have far more extensive experience in government, the decline of the League means Meloni will be the central figure in the new administration and she will have a window of opportunity to implement her policy agenda. Key targets are likely to include cutting taxes on energy, renegotiating Italy’s EU recovery funds, responding to the energy crisis, and eliminating the so-called ‘citizens’ income’ subsidy for low-income earners that was introduced by the Five Star Movement in 2018.

Some of these proposals will provoke significant opposition. The citizens’ income is popular with large sections of the electorate, notably in southern Italy where there are a large number of beneficiaries. The Five Star Movement, which won a convincing third place in the election and received substantial support in the South, is particularly well placed to argue against this policy.

Meloni will need to mediate between her coalition partners, building a dialogue with Berlusconi and Salvini, who both have very different positions on domestic and foreign policy. The choice of ministers in key areas such as the economy, defence, foreign policy, and the interior will be an important indication of the political agenda, governability, and stability of the new government.

A return to politics?

Since the Tangentopoli corruption scandal in the early 1990s, and in tandem with a growing economic and social decline, Italian politics has suffered from acute institutional weaknesses and a complex electoral law. This has given rise to what the historian Donald Sassoon terms the ‘Italian technocratic anomaly’, where a series of technocratic prime ministers have competed with a tumultuous set of party leaders, including Silvio Berlusconi, Matteo Renzi, Beppe Grillo, Matteo Salvini, Giuseppe Conte, and now Giorgia Meloni.

It will now fall on Meloni and her coalition to guarantee institutional continuity and govern jointly “for all Italians”, as she pledged to do following her victory. If she succeeds, Italy may witness a lasting ‘return to politics’. Failure, on the other hand, could potentially lead to another technocratic government and a continuation of the pattern we have seen over the last three decades.

Implications for Europe

If the defeat of Marine Le Pen in this year’s French presidential election prompted a wave of relief in European capitals, Meloni’s victory has raised new red flags. Her words of admiration for Viktor Orban and her special bond with the Spanish far-right party Vox will have done little to assuage these fears.

The Italian election came shortly after the far-right Sweden Democrats’ strong performance in the Swedish general election, where it finished in second place. There are now signs that populism is re-emerging as a force in European politics. Meloni’s success, alongside that of the Five Star Movement, suggests Europe is still very much fertile ground for populist movements seeking to capitalise on the social and economic anxieties of citizens.

As Europe enters another precarious moment driven by the increasingly unpredictable war in Ukraine, the post-pandemic recovery, and an inflation and energy crisis that will deepen as winter approaches, thoughts may soon turn again to the EU’s democratic deficit. The EU would be well advised to heed the lessons from Italy by engaging with its citizens directly and working to address their grievances.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Vox España (Public Domain)