The UK is set to vote on its EU membership on Thursday. Which arguments have resonated most with voters throughout the campaign? Sara Hobolt and Christopher Wratil present survey evidence indicating that immigration and the economy have been the most prominent topics. Undecided voters have, however, been less moved by these issues and cite misinformation and distrust in politicians as their reasons for remaining on the fence.

Voters face a seemingly simple choice in this referendum: for the UK to remain in or leave the EU. But the choice between continued membership or Brexit touches upon a number of complex political, economic and identity issues, and no one can fully foresee the consequences of either outcome. Hence, the key battle for the Remain and Leave campaigns has been to “frame” what the referendum question is about. From the outset, the battle lines have been clearly drawn: the economy vs. immigration. The messages have also been clear: vote remain to avoid the economic disaster of a Brexit (“A leap in the dark”) or vote leave to regain control of British borders and restrict immigration (“Take back control”).

Yet we know less about how these arguments resonate with the British public. What are the main arguments that matter to voters? And what are the reasons that some people have yet to make up their minds? To answer these questions, we conducted a survey of a representative sample of over 5,000 British citizens (carried out by YouGov) and asked their opinions about the referendum. People in the survey were asked to think about the arguments they have personally heard during the referendum campaign and summarise the main argument in their own words.

When analysing these thousands of open-ended responses, we find that immigration and the economy emerge as the main arguments. We find around nine distinct arguments mentioned by voters that centre on immigration, sovereignty, the economy, lack of information, and distrust in the government. These are summarised in Figure 1 below. Interestingly, a number of other issues often central to the debate on European integration, notably democracy and environmental protection, do not appear as prominent arguments for or against membership in the minds of voters in this referendum debate.

The public is clearly sharply divided in what it considers to be the main issue of the referendum. As Figure 1 shows below, the two key arguments that resonate more with remain voters than with leave voters relate to the economy, specifically the loss of security and economic stability in the event of Brexit and the economic benefits of EU membership. As one participant in the survey responded: “The huge economic advantage of being in the EU, confirmed by multiple economic organisations, business leaders and the scientific community.”

In contrast, leave voters highlight concerns about immigration much more frequently than remain voters, as expressed by one respondent: “Immigrants flooding into the country if we don’t regain control of our own borders”. Another key argument for leave voters is lack of trust in David Cameron and his government (“A lot of lies from Dave”). We know from other referendums on European integration that lack of trust in the incumbent government can boost the Eurosceptic vote.

Figure 1: Main arguments for remain and leave voters

Source: Original poll conducted by YouGov between 9-11 May 2016 with financial support from the British Academy/Leverhulme Trust (SG153370) . The figure shows the results from Structural Topic Model with k = 9 topics and demographic, socioeconomic, and political covariates. It depicts differences in topic proportions between Leave and Remain voters (pr(Leave) – pr(Remain)); estimated with “stm”-package in R.

Immigration or the economy? A divided public

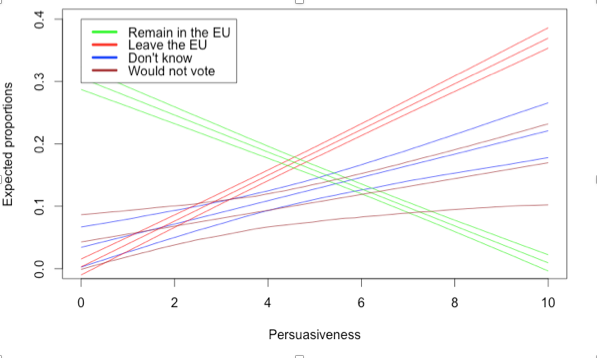

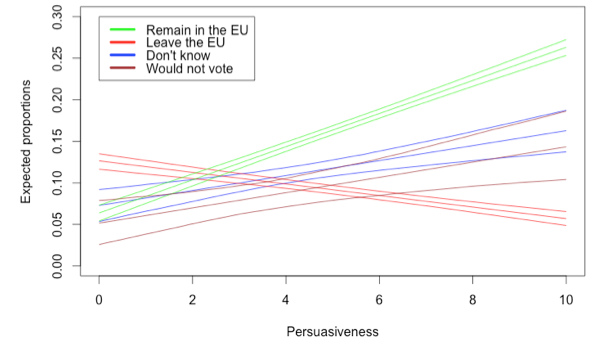

How convincing were these arguments for different types of voters? Respondents in our survey were asked to rate the arguments they had heard in terms of their persuasiveness on a scale from 0 to 10. Looking first at the immigration argument, we see that this clearly divides the British public: leave voters find the argument highly persuasive while remain voters do not. Interestingly, undecided voters also tend to find the argument persuasive, although less so than those who have already decided how to vote.

Figure 2: How persuasive is the immigration argument?

Turning to the main economic argument, we see that the picture is reversed: remain voters find it persuasive while leave voters do not; although the differences are less stark than when it comes to immigration, which is clearly a more divisive issue. Again, undecided voters are ready to be persuaded by the economic argument.

Figure 3: How persuasive is the ‘economic benefits of the EU’ argument?

Winning over the undecided

How do undecided voters, and those who intend to stay at home on Thursday, differ from other voters, and what arguments may sway them? Most undecided voters complain that the campaign has not been characterised by substantive arguments and facts, but rather by misinformation, scaremongering and untruths. As one person noted: “I have absolutely zero interest in the whole sorry saga. Politicians on neither side can be trusted to tell the truth”; and another: “I am confused. We hear totally opposite opinions from so-called experts, all of whom have vested interests”.

Lack of impartial information thus seems to be a key reason why many voters are still undecided. They have been exposed to the opposing arguments, yet they find it hard to know which side to trust. Studies of previous referendums have also shown that undecided voters tend to be more risk averse and thus more likely to vote for the status quo when they finally decide. This should favour the remain side on Thursday. Although much will depend on whether the fear of immigration or the fear of economic instability is seen as the greater threat. Some voters may also be so dismayed and confused by the nature of this campaign, and the way in which politicians have put forward their arguments, that they decide to stay at home altogether.

About the authors

Sara Hobolt is the Sutherland Chair in European Institutions and professor at the LSE’s European Institute and Department of Government. She’s a leading expert on European referendums, elections and public opinion.

Christopher Wratil is a PhD candidate at the European Institute of the LSE and a member of FutureLab Europe. His research focuses on citizen representation in the European Union.