The “Qatargate” scandal has focused attention on the impact of lobbying on EU policymaking. Drawing on a new study, Alexander Katsaitis examines what we know about the financial donations received by EU level political parties and foundations.

Money talks, as the saying goes. Yet, until recently the link between money and politics in the European Union received relatively little attention. All this changed, however, with “Qatargate”, a cash-for-influence political scandal involving non-state actors, members of the European Parliament and foreign governments.

The scandal highlighted the prominence of financial donations in EU lobbying, their potential adverse effects on institutional legitimacy and the changing nature of transnational politics. The first step to better understanding the link between money and EU politics is to systematically track and assess the financial donations received by the EU’s main political actors: its political parties. This raises two central questions: Who donates to EU political parties? And what do these donations mean for EU politics?

Financial donations and political parties in the EU

In a recent study, I seek to answer these questions. To understand who the donors and recipients of financial donations are, I assess the budgets of EU level political parties and foundations recognised by the Authority for European Political Parties and European Political Foundations. Focusing on donors’ organisational structures and their geographic location, I observe some interesting patterns.

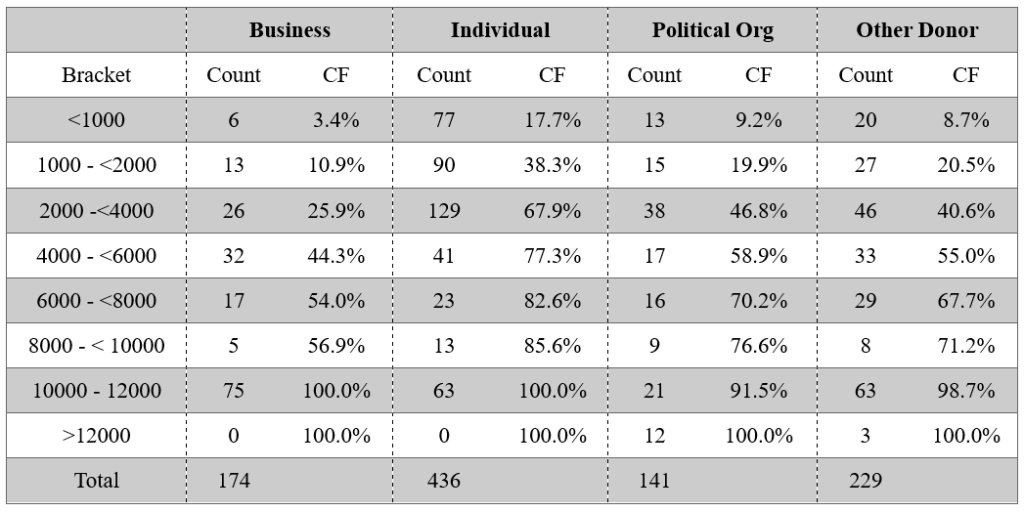

Table 1: Cumulative frequency distribution of the amount of donations political parties received from different donors

Note: Brackets indicate the value of donations in euros. The count is the number of donations, while CF refers to cumulative frequency. For more information, see the author’s accompanying article in European Union Politics.

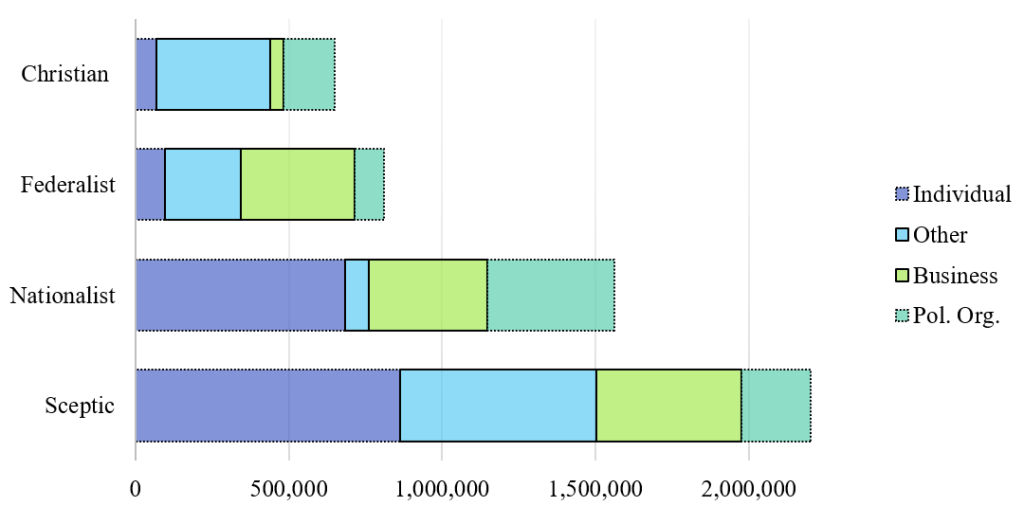

Interestingly, individuals are the largest contributors in terms of the number of donations and total amount. Moreover, the primary recipients of individuals’ donations are nationalist and Eurosceptic parties.

Figure 1: Donations received by parties representing a specific political agenda from donors with different organisational characteristics

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper in International Affairs.

Business has a strong presence in Brussels and has the resources to mobilise. However, it has largely decided not to use financial resources to directly support parties in Brussels. When it does contribute however, it does so by providing donations close to the regulated legal limit.

Business donors tend to donate to pro-market and integration parties (shown as “Federalist” in Figure 1), providing on average much higher donations than other donors. “Other organisations”, a mixed category consisting of groups such as civil society organisations, cultural associations and religious organisations, donate primarily to political parties with a Christian-democratic agenda.

Social cleavages, postfunctionalism and European Integration

From this analysis, we can draw three main lessons. First, a financial donation expresses a commitment made by a donor towards a political party and reflects support towards a particular agenda. Past research highlights that donors are more likely to provide support to parties closer to their political beliefs and that have the potential to influence policy. Thus, we tend to observe social cleavages reflected in financial donations. My analysis supports this.

All donations are received by parties that are on the centre and extreme right of the political spectrum. This is not to say that parties on the left do not receive financial support. It is possible that other parties may be receiving financial support through party memberships or financial donations at the national level. Nevertheless, in terms of financial donations directed towards EU level parties, the data reveals a distinct post-functional cleavage between business and federalists versus Eurosceptics, nationalists and citizens.

As EU policy grows ever more complex and spills over across layers of interconnected and integrated areas, even regulatory decisions can have significant re-distributive effects at the national level. This produces winners and losers not only between states but also within them. In turn this leads to common political conflicts across social groups, across countries and across levels of government. This not only establishes a common transnational political agenda but also provides substantial reason to support it.

Anti-integration positions can take the form of calls for disintegration. Such political agendas are now receiving transnational support in the form of financing. For now, it is primarily small and medium sized parties actively seeking and welcoming such financial support. However, as political competition increases in Brussels, there is little reason to assume that things will stay the same. We could easily see larger parties actively seeking additional financial support from donors down the line.

International parliamentary institutions and political finance

Second, from an international relations perspective, the European Parliament represents a form of international parliamentary institution. In the context of global governance, international parliamentary institutions are meant to support the political legitimacy of international organisations against the technical authority they extract from the national level. However, international parliamentary institutions such as the European Parliament are not perceived as institutions that connect to transnational grassroots socio-political movements based at different levels.

My results suggest that we may need to update our conceptual models, considering that international parliamentary institutions can (and do) serve as vehicles for partisan activity that links socio-political movements across borders and levels with the policymakers within the institution.

In addition, these political movements may actively aim to delegitimise the institution’s political legitimacy and by implication that of the wider international organisation. In this case, anti-integration political parties can receive financial support to campaign, mobilise and de-legitimise the EU. Simply put, it may be optimistic to hold normative expectations that the European Parliament (or any international parliamentary institution) will generate growing political commitment towards the EU (or its respective international organisation) because of rational expectations linking technical efficiency with public support.

The tip of the iceberg: research and regulation

Finally, this analysis addresses only part of a much wider field covering political finance in the EU. Further work assessing the link between political donations and policymaking influence, as well as politics, donations and corruption at the EU level is necessary. Especially when we consider the expanding role of EU politics in a politicised Europe. Moreover, identifying the network of political donations across Europe is necessary to accurately map transnational movements as well as address security concerns linked to foreign influence. The chain of political integrity is only as strong as its weakest link.

Comparative work examining how different types of international parliamentary institutions receive financial support may offer a fruitful path for appreciating the interaction between political mobilisation and institutional integrity within global governance. Furthermore, this can help inform regulatory updates on financial donations, political parties and non-state actors.